Vilca, Anandenandhera colubrina

Tello Obelisk, Chavín de Huántar, Peru

Chavin Culture, Andes, and throughout South America

1. Name

Vilca, also known as “cebil,” is a South American psychoactive snuff powder containing the prepared pods of the Anadenanthera colubrina tree—a tree resembling the Anadenanthera peregrina tree from which is made a Caribbean psychoactive snuff powder called “yopo” or “cohoba.” While Anadenanthera colubrina is widespread in South America, this entry will favor the term “vilca” and the ancient Chavin culture from the northern Andean highlands of Peru, which flourished 900-200 BCE. Anadenanthera colubrina snuff, or vilca, continues to be used throughout South America, especially in Peru, suggesting a duration of continued psychedelic plant use.

Cultural uses of vilca include divination to gain knowledge and insight, therapeutic applications to treat illness, and as a physical purgative; vilca experiences in Ancient times include interaction with supernatural agents. Material evidence of early vilca use in ancient ceremonial centers was social, not isolated ecstatic experiences by individuals. [1] Divination is performed by consuming vilca snuff powder and interpreting the visionary effects. Its therapeutic properties expel sickness, especially respiratory illnesses: Vilca functions as an expectorant, balances humors, and treats cholera. The inhaled powder functions as a physical purgative, not unlike the vomiting common with drinking Ayahuasca or Yagé brews.

The main psychoactive principles in vilca are bufotenine and N,N- dimethyltryptamine (DMT). Bufotenine is a naturally occurring alkaloid related to the neurotransmitter serotonin—they share tryptamine as a parent molecule—that naturally occurs in specific species of toads of the genus Bufo and a wide range of plants. DMT is an active, naturally occurring psychedelic compound that strongly interacts with serotonin receptors in the brain; it is found in a variety of Amazonian plants.

Anadenanthera colubrina seed-pod snuff has a range of names throughout South America. Vilca tawri is a regional powder in Peru that, in addition to Anadenanthera colubrina, contains the non- psychedelic, high-protein beans of Andean Lupinys mutabilis, known as “maca” or “macay.” In the Quechua and Aymara languages, the word “vilca” signifies sacredness. Other South American Indigenous names for Anadenanthera colubrina snuff include “aimpa,” “hatax,” and “kuripai.” [2] Compiled and published in Lima circa 1612, the Dictionary of the Aymara language: First and Second Parts, explains: “Villca: The sun as it is was said in antiquity and now they said inti . . . Villca: Shrine dedicated to the sun and other idols . . . Villca is also a medicinal thing, or thing given to drink as a purge, for sleeping, and in the sleep would come the thief who had taken the estate belonging to the one who drank the purge, and recover his state; it was a sorcerer’s deception.” [3]

2. Introduction and Artwork

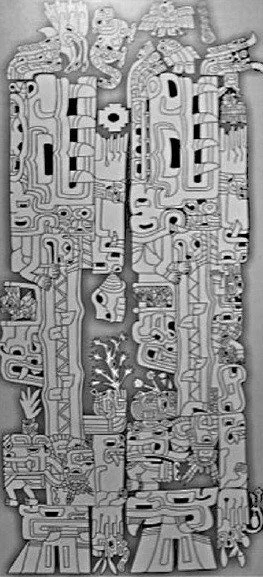

The Tello Obelisk found in the ancient complex of Chavín de Huántar in Peru is a four-sided, vertical depiction of a zoomorphic crocodile being, but the overall image stretches across all four sides of the obelisk: the two broader sides depict each horizontal side of the crocodile’s body, and the narrow two images connect the sideview images and fill the obelisk with a range of images. The images should be considered beings, if not persons. (Image 1) The obelisk depicts three types of images: phytomorphic plant imagery, such as seeds, leaves, and trees; zoomorphic animal imagery, such as birds, felines, shells, and crocodiles; and anthropomorphic human imagery. The central crocodile figures could be accompanied by or made up of these human, animal, and plant images. Heads of animals may appear human, but are marked as animals by bearing claws and fangs. Considering their animal-human hybridity, these may be supernatural figures. Some of the animal and supernatural figures can be interpreted to bear psychoactive plants, such as those from the genus Brugmansia of flowering nightshade, huachuma, or the San Pedro Cactus (Trichocereus pachanoi / Echinopsis pachanoi), and vilca (Anadenanthera colubrina), even though the vilca-producing plant does not grow in the area of Chavín de Huántar. All the images are reproduced from Maarten H. Dikkers’s The Tello Obelisk: A Very Detailed Summary on his Images (2024). [4] It should be remembered that interpreting the images on the Tello Obelisk has been hotly debated and remains without definitive conclusions.

Image 1 is a photo of the physical obelisk. Image 2 reproduces J.W. Rowe’s paper reproduction of the obelisk’s imagery. In image 3, Maarten H. Dikkers has colored component images in brown, olive, purple, and red. This entry will use Dikkers’s coloring to identify, isolate, and describe three specific images analyzed below. Lastly, Image 4 reproduces a depiction of the obelisk displayed at the Chavín National Museum that presents the images without any of the secondary lines or symbols. Images 1, 2, and 3 combine the four sides of the obelisk in Image 1 into a single vertical image that depicts the four sides all together.

In a ground-breaking study, Mulvany de Peñaloza highlights a zoomorphic animal representation accompanied by a psychedelic plant, likely a flowering nightshade. To the bottom right, below the crocodile’s brown bottom leg, is perhaps an olive-colored vizcacha de la sierra (Lagidium viscacia), a mountain-dwelling rodent belonging to the chinchilla family, and from its mouth comes a red phytomorphic plant image. Peñaloza identifies the plant as Brugmansia [6], a genus of psychoactive nightshade plants with pendulous flowers, though Brugmansia plants are considered hallucinogens and delirogenics and not considered psychedelics. Scopolamine, the psychoactive principle in Brugmansia plants, works with different neuroreceptors and is more toxic than psychedelic plants and substances.

Further to the left of the nightshade-bearing animal, under the other brown bottom leg of the crocodile, is another zoomorphic animal head. From its mouth emerges a plant representation with three leaves and several seeded pods, resembling pod-shaped fruits. Perhaps these seedpods, clearer to see in Image 2, are cross-cut Anadenanthera colubrina seeds and seedpods, the main ingredient in vilca, and the three leaves correspond to the variegated foliage of the Anadenanthera colubrina. [7]

Toward the center of the image, at the center of the crocodile’s body, are two feline-looking, supernatural beings with L-shaped, yellow bodies topped with zoomorphic animal heads marked by fangs and red lips; they are both connected to phytomorphic plant images that resemble trees at first glance. One of the figures has a white headdress, and a branching white plant emerges from its mouth. The second figure is depicted with a purple background, and three leaves seem to emerge from its head in that dark background. The lines of both figures are easier to discern in Image 2. Peñaloza argues that both these plants represent a secondary stem of the San Pedro cactus; further analysis reveals that Anadenanthera colubrina (vilca) and Trichocereus pachanoi/Echinopsis pachanoi (Huachuma or San Pedro cacti) could be both or either of the plants represented along with these two supernatural animal heads; both plants have psychedelic properties. [8]

Peñaloza’s hypothesis was initially considered speculative and without sufficient archeological evidence, but recent research about material culture in Chavín de Huántar supports Peñaloza’s findings. It provides direct evidence for the use of Anadenanthera colubrina and other psychedelic plants in the Andean region and among the cultures that created the Tello Obelisk. Even if Anadenanthera colubrina does not naturally grow there, it can be found growing twenty-five miles from the ceremonial center. [9] Plants with psychoactive and psychedelic properties were used by the Chavin people in institutionalized rituals and were not limited to individualized contexts of ecstatic shamanism. [10] Analysis of the Tello Obelisk suggests that psychoactive plants may have been used throughout the region during the Early Horizon phase of Andean History (1200-500 BCE), especially when the Chavin flourished (900-200 BCE).

3. Geographical distribution

Anadenanthera colubrina thrives south of the equator, and its active entheogenic use is documented throughout the Central and Northern Andes. The tree can be found in Paraguay,Bolivia, and Peru, reaching as far north as the Marañon valley on the western slopes of the Andes. It is found throughout the northern Argentinian-Chilean mountain plateau of Puna, and it is common in the Argentinian provinces of Salta, Jujuy, Catamarca, Tucumán, and Misiones. [12] Its cultivation and common trade, even by groups that do not use the term vilca, affirm its importance in ritual and healing practices across regions and across cultural traditions in the Americas. [13]

4. Primary Sources

Colonial records and ancient material culture document vilca (Anadenanthera colubrina) as a sacred plant throughout the Andes. Sixteenth-century Spanish sources particularly note the use of vilca for divination. Archeological evidence suggests the ritual use of vilca as early as 4,500 years ago in Northwest Argentina and surrounding areas.

In 1571, the Spanish jurist and scholar Polo de Ondegardo wrote the first historical literary reference to the psychoactive properties of vilca. “Those who wish to know an event of things past or of things that are to come ... invoke the demon and inebriate themselves and for this practice in particular make use of an herb called vilca, pouring its juice in chicha or drinking it by another way. Note that even though it is said that only old women practice the craft of divination and of telling what happens in remote places and to reveal loss and thievery, it is also used today by Indians, not only by the old but also by the young.” [15] In 1580, the Spanish chronicler Cristóbal de Albornoz describes the ritual use of vilca as a snuff powder in the southern Andean region. [16]

Paraphernalia for the preparation and use of vilca as a snuff powder and as an inhaled smoke are well documented. Ceramic smoking pipes found in caves contain vilca seeds in their bowls and bends. Snuff tables, snuff pipes, and snuff tubes were discovered west of the Andes in the Atacama Desert in Chile. Six bird-bone artifacts containing chemical and microbotanical traces of psychoactive plants—including Anadenanthera colubrina and Nicotiana rustica—were recently discovered in Chavín de Huántar in Peru, an important Andean ceremonial center and the site of the Tello Obelisk described above. [17]

5. Interpretation

The Chavin culture—which arose during the Early Formative period of Andean History (1200vBCE to 200 BCE) and flourished from 900 to 200 BCE—exhibited significant influence in the Andes through their material and ritual culture, including intricate art, ceramics, and rituals, all of which are connected to vilca (Anadenanthera colubrina). Therefore, vilca is a potent aspect to examine when interpreting early sociopolitical formation and differentiation in the historical development of Andean cultures. During the Early Formative period in the Andes, agriculture, textile art, and metallurgy developed. Also developed during this time were ceramics, which were produced close to the ceremonial center and profoundly augmented religious practices, including the use of vilca.

At Chavín de Huántar, rituals that included vilca use took place inside restricted spaces like ceremonial buildings and around monumental structures such as stelae and obelisks. Institutional uses of Anadenanthera colubrina produced hierophanies that ensured ritual efficacy and increased the credibility of the hosts in these rituals. In turn, these potent rituals strengthened the power of ritual specialists and priests, further facilitating social differentiation through prestige. [19] These spaces and structures, in turn, displayed the iconography of supernatural beings and their lore. Chavín de Huántar was a major center of public ritual activity. The ritual use of vilca was not limited to individual ecstatic experiences but was a socially consumed and socially structured aspect. “The site is sometimes presumed to have been a peaceful pilgrimage center that attracted devotees from across the Central Andes.” [20]

Privileged access included entering and using these restricted sacred spaces, actively participating in ceremonies, and ritually experiencing psychedelic substances that facilitate communication with sacred forces and supernatural beings. These rituals and spaces generated and sustained a vibrant ritual culture, but that ritual culture was structured by access according to prestige. [21] Vilca, often consumed and prepared using the Chavins’ vaunted ceramic pipes and tools, ensured ritual efficacy, and thereby its use strengthened the power of ritual specialists and priests. In this way, these potent, entheogenic rituals created and affirmed social differentiation, but also strengthened the collective feelings of the pilgrims.

6. Implications

Vilca (Anadenanthera colubrina) is considered a gateway to a visionary world, but it is also a medicine and a symbol related to light and the sun throughout the Andean region. In Northwestern Argentina, ceramic pipes found in caves suggest that vilca has been smoked there for 4,500 years. Vilca continues to be used today in that region, possibly making vilca the longest documented continued use of a sacred plant with psychedelic properties by humans worldwide.

Studying material culture is essential to avoid hasty generalizations and incomplete speculation regarding cultural and spiritual uses of psychedelic plants. At the ceremonial center of Chavín de Huántar in Peru, recent archeological findings highlight the significance of studying material culture to achieve solid evidence about the ritual consumption of psychedelic plants, especially when previous studies have been largely speculative. The use of Anadenanthera colubrina at Chavín de Huántar has been proposed for some time. However, the discovery of chemical and microbotanical residues of vilca on ritual paraphernalia at Chavín de Huántar and throughout the Andes grounds that speculation in historical fact.

References

[1] Rick, John. W, Verónica. S. Lema, Javier Echeverría, Giuseppe Alva Valverde, Daniel A Contreras, Oscar Arias Espinoza, Silvana A. Rosenfeld, and Matthew P. Sayre. “Pre-Hispanic ritual use of psychoactive plants at Chavín de Huántar, Peru.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences-PNAS 122, no.19, (2025): 8-9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2425125122

[2] Torres, Constantino. M., and Repke, David. B. Anadenanthera: Visionary Plant of Ancient South America. (Haworth Herbal Press, 2006), 8-9.

[3] Torres, Constantino. M., and Repke, David. B. Anadenanthera: Visionary Plant of Ancient South America. (Haworth Herbal Press, 2006), 27.

[4] Dikkers, Maarten H. “The Tello Obelisk, a Very Detailed Research on His Images.” The Tello Obelisk, 2024. Academia.edu. https://www.academia.edu/122407177/The_Tello_Obelisk_a_very_detailed_research_on_his_images

[5] Sayre, Matthew, P. (2018). “A synonym of Sacred: Vilca use in the Preconquest Andes.” In Ancient Psychoactive Substances, ed. Scott. M Fitzpatrick (University Press of Florida, 2018), 270. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvx076mt.14.

[6] Peñaloza, Eleonora Mulvany de. “Motivos fitomorfos de alucinógeno en Chavin.” Chungara, no. 12 (1984): 61.

[7] Peñaloza, Eleonora Mulvany de. “Motivos fitomorfos de alucinógeno en Chavin.” Chungara, no 12 (1984): 65.

[8] Peñaloza, Eleonora Mulvany de. “Motivos fitomorfos de alucinógeno en Chavin.” Chungara, no 12 (1984): 70.

[9] Rick, John. W., Verónica. S. Lema, Javier Echeverría, Giuseppe Alva Valverde, Daniel A,Contreras, Oscar Arias Espinoza, Silvana A. Rosenfeld, and Matthew P. Sayre. “Pre-Hispanic ritual use of psychoactive plants at Chavín de Huántar, Peru.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 122, no.19, (2025): 7.

[10] Rick, John. W., Verónica. S. Lema, Javier Echeverría, Giuseppe Alva Valverde, Daniel A,Contreras, Oscar Arias Espinoza, Silvana A. Rosenfeld, and Matthew P. Sayre. “Pre-Hispanic ritual use of psychoactive plants at Chavín de Huántar, Peru.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 122, no.19, (2025): 9.

[11] Cosenza, Luciano, Eliana Moya, María Franco, Mariana Brea and Darién Prado. “Anatomía de la madera y el carbón de Anadenanthera colubrina var. Colubrina. (Leguminosae, Caesalpinioideae).” Darwiniana, no 10. (2022):106. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14522/darwiniana.2022.101.999

[12] Torres, Constantino. M., and Repke, David. B. Anadenanthera: Visionary Plant of Ancient South America. (Haworth Herbal Press, 2006),7.

[13] Sayre, Matthew, P. (2018). “A synonym of Sacred: Vilca use in the Preconquest Andes.” In Ancient Psychoactive Substances, ed. Scott. M Fitzpatrick (University Press of Florida, 2018), 281.

[14] Rick, John. W., Verónica. S. Lema, Javier Echeverría, Giuseppe Alva Valverde, Daniel A,Contreras, Oscar Arias Espinoza, Silvana A. Rosenfeld, and Matthew P. Sayre. “Pre-Hispanic ritual use of psychoactive plants at Chavín de Huántar, Peru.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 122, no.19, (2025):8.

[15] Torres, Constantino. M., and Repke, David. B. Anadenanthera: Visionary Plant of Ancient South America. (Haworth Herbal Press, 2006), 26.

[16] Schultes, Richard Evans., Albert Hofmann and Christian Rätsch. Plants of the Gods.Their Sacred, Healing and Hallucinogenic Powers. (Healing Arts Press, 1992), 120.

[17] Rick, John. W., Verónica. S. Lema, Javier Echeverría, Giuseppe Alva Valverde, Daniel A,Contreras, Oscar Arias Espinoza, Silvana A. Rosenfeld, and Matthew P. Sayre. “Pre-Hispanic ritual use of psychoactive plants at Chavín de Huántar, Peru.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 122, no.19, (2025): 3-4.

[18] Rick, John. W., Verónica. S. Lema, Javier Echeverría, Giuseppe Alva Valverde, Daniel A,Contreras, Oscar Arias Espinoza, Silvana A. Rosenfeld, and Matthew P. Sayre. “Pre-Hispanic ritual use of psychoactive plants at Chavín de Huántar, Peru.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 122, no.19, (2025), 4.

[19] Rick, John. W., Verónica. S. Lema, Javier Echeverría, Giuseppe Alva Valverde, Daniel A,Contreras, Oscar Arias Espinoza, Silvana A. Rosenfeld, and Matthew P. Sayre. “Pre-Hispanic ritual use of psychoactive plants at Chavín de Huántar, Peru.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 122, no.19, (2025), 8-9.

[20] Sayre, Matthew, P. (2018). “A synonym of Sacred: Vilca use in the Preconquest Andes.” In Ancient Psychoactive Substances, ed. Scott. M Fitzpatrick (University Press of Florida, 2018), 270.

[21] Rick, John. W., Verónica. S. Lema, Javier Echeverría, Giuseppe Alva Valverde, Daniel A,Contreras, Oscar Arias Espinoza, Silvana A. Rosenfeld, and Matthew P. Sayre. “Pre-Hispanic ritual use of psychoactive plants at Chavín de Huántar, Peru.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 122, no.19, (2025), 8-9.

Image 1. Tello Obelisk. The four sides of the Tello Obelisk displayed in vertical presentation. All the other images in this entry are composite reproductions that combine the four sides of the obelisk into a two-dimensional depiction. Photo by Maarten H. Dikkers (2024).

Image 2. Tello Obelisk. The four sides of the Tello Obelisk recorded on paper by J.W. Rowe in the 1960s. Note the ways that images on the four sides overlap.

Image 3: Tello Obelisk. Images colored by Maarten H. Dikkers, July 2024. The shapes of the separate beings highlighted by color. Olive is the color of the composite animal beings and the crocodile; the red lips help to separate the individual entities.

Image 4: Tello Obelisk. The Tello Obelisk without hieroglyphs, meaning that non-image lines are not shown in this representation. Chavín National Museum. [5]

Image 5. Anadenanthera colubrina var. colubrina. A, specimen from Urquiza Park, Paraná, Entre Ríos. B, trunk with mamelons. C, branch with leaves and fruits. D, detail of leaves and flowers. E, fruits. F, seeds. G, insertion of leaflets on the rachis. H, leaflet with closed reticulate venation. I, detail of hairy rachis and rachis. Scales: E = 45mm; F, G = 10 mm; H, I = 1 mm.” Translated from Spanish. [11] ojs.darwin.edu.ar/index.php/darwiniana/article/view/999/1248

Image 6. Map of pre-Hispanic use of Anadenanthera colubrina var cebil and Nicotiana in the Central and Southern Andes based on microbotanical and chemical evidence. [14] (Rick et al 2025, 8)[AU1]

Image 7. Scientific photographs of ritual paraphernalia containing chemical and/or microbotanical residues of vilca and/or Nicotiana. [18]

Image 8. Anadenanthera colubrina var. cebil observed in Salta, Argentina by janetchambi, documented on iNaturalist. inaturalist.org/observations/44008012