Salvia divinorum, Apipiltzin (Nahuatl), Ská Pastora (Mazatec)

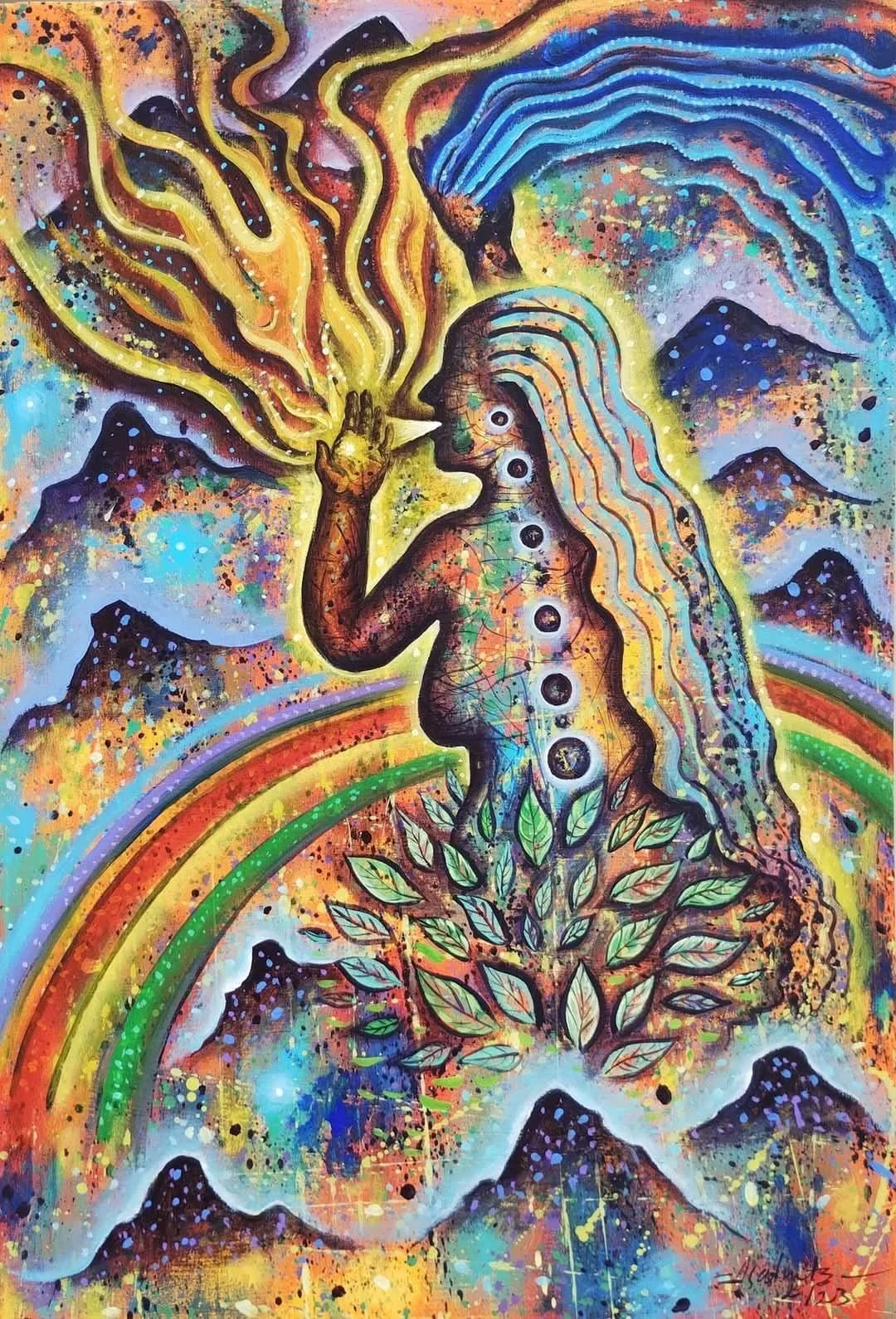

“Birth of the Rainbow and the Shepherdess Mother” (2023) by Asunción Alvarado

Nahua and Mazatec Cultures

1. Name

Ská pastora is a Mazatec name for Salvia divinorum, a green, leafy plant in the mint family that bears white flowers blooming from purple calyces. (Image 2, Image 4) The Mazatec-language name ská pastora is a hybrid and cross-cultural term: the Mazatec first syllable, ská or xcà, can be translated as “leaf,” and the Spanish word pastora can be translated as “shepherdess.” One hypothesis for an Aztec historical name in the Nahuatl language for Salvia divinorum is pipiltzintzintin or pipiltzintzin. This entry will focus on the Mazatec culture and favor the name “ská pastora.”

In contemporary Mazatec culture, Salvia divinorum is known by the names “hojas de la Pastora,” meaning “leaves of the shepherdess,” and “hojas de Maria Pastora,” meaning “leaves of Mary the Shepherdess.” In Christian traditions, however, the Virgin Mary is not thought of as a “shepherdess pastora.” This shepherdess pastora could be a survival of the pre-Christian dueño de los animales, “The Lord of the animals,” who figures large in folk traditions of Native Americans. [1]

2. Introduction and Artwork

Asunción Alvarado’s 2023 painting Birth of the Rainbow and the Shepherdess Mother depicts a personification of ská pastora as a spectacular and mystical female figure. (Image 1)

At the bottom of the painting, a set of four mountains is surrounded by mist, which is considered alive in the Mazatec worldview. The birth of a rainbow crosses from the left side to the right. Between the rainbow and the mountains is a bush with salvia leaves, presumably ská pastora.

The female figure, who personifies ská pastora, speaks out with yellow breath that transforms into fire as it crosses her hand at the end of her bent arm. Her long hair flows down to cover her back, and at her hips it resembles a luminous waterfall. Toward the top of the painting, flowing to the right from her hand at the end of her extended right arm, is a stream of rippling water.

A set of seven mountains is found towards the top of the painting—four to the left and three to the right. Mountains emerge from the sacred woman’s breath, from the rippling water stream, and from herself as the personification of ská pastora.

The artist of the painting, Asunción Alvarado, explains: “Among the ways taught to us by our ancestors is the ceremonial use of the mother shepherdess to seek health and emotional balance, as well as to communicate with the entities and guardians of this sacred plant. The wise men and women, since the moment they uproot it, sing to it, offer it gifts, speak to it affectionately, and ask it to allow itself to be used in the ceremony for healing, seeking, and mediating the problem that the patient is going through. This work reflects the spirit of the mother shepherdess, managing fire and water, together with the magic of the rainbow, as she guards and cares for the Mazatec mountains.” [2]

3. Geographical Distribution

The natural growth of Salvia divinorum is confined to Mazatec country and the immediately contiguous areas of Cuicatec and Chinantec in Oaxaca State, Mexico, but the plant is also known and used elsewhere. (Image 2) The Salvia divinorum plant is native to Mazatec areas of the Sierra Madre Oriental mountain range. It grows naturally in tropical rainforests at altitudes ranging from 300 to 1,800 meters, or approximately 1,800 to 6,000 feet. [3] This limited geographic habitat ranks Salvia divinorum among the rarest of psychoactive plants; despite its natural scarcity, the plant is not rare, for it is reproduced by cuttings: Salvia divinorum is cultivated worldwide.

4. Historical Sources and Anthropological Evidence

The ancient Nahuas (Aztecs) knew a plant called pipiltzintzintli, meaning “the purest little prince” in the Nahuatl language, and this could be ská pastora. Stored at the National Archive in Mexico City, the Catholic Church has Inquisition files from the years 1696, 1698, and 1706 that mention a plant named pipiltzintzin, a name closely resembling the Nahuatl spelling of pipiltzintzintli. These files hint at the sacred plant’s intoxicating effects, but the identity of the plant in these records has not been conclusively proven.

Richard Evans Schultes and Albert Hoffman [6], as well as Mercedes de la Garza [7], hypothesize that pipiltzintzintli is Salvia divinorum. However, José Luis Díaz has challenged this hypothesis. Based on the work of Friar Antonio Alzate (1772), Díaz argues that pipiltzintzintli is cannabis imported from Asia that was used as hemp and also consumed for divination purposes. [8] According to Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán, “the Inquisition archives mentioned a cultivated plant that causes hallucinations. It is dried and drunk diluted in water. They said bad things and talked nonsense with it.” [9] The plant was used by Native Mesoamericans to diagnose illnesses, and the Holy Inquisition forbade its use; Beltrán explains that those who carried the plant as an amulet were persecuted. [10] However, no researcher has conclusively identified the pipiltiztzintli plant.

Historical and ethnographic research on ská pastora in contemporary Mexico dates back to 1938, with the work of anthropologist Jean Bassett Johnson, who recorded the use of Salvia divinorum among the Mazatecs in Oaxaca. [11]. Ethnobotanical study of Salvia divinorum use among the Mazatecs documents their close and extensive relationship with the plant and the historical continuity of Ska Pastora being used therapeutically and for divination. [12]

It is important to remember that contemporary ritual practices of the Mazatecs, and many other Mesoamerican cultures, reflect a spiritual synergy that combines elements from Mesoamerican cosmology and the Catholic worldview, just as the name “ská pastora” combines a Mazatec word with a Spanish word.

5. Interpretation

To better understand ská pastora’s social and cultural significance, it is necessary to explain the plant’s healing, divination, and creative uses.

For centuries, Mazatec healers, known as “chotaj chinej,” have long known about ská pastora’s therapeutic properties. According to the chotaj chinej María Sabina: “When I am in the time that there are no mushrooms and want to heal someone who is sick, then I must fall back on the leaves of Pastora. When you grind them up and eat them, they work just like the niños. But, of course, Pastora has nowhere near as much power as the mushrooms.” [13] The Mazatec people broadly consider ská pastora to be a deity and also a female healer, and it is necessary to listen carefully to her. Another chotaj chinej, Julia Aurelia Palacios, states that “You have to chant the voice of the leaf.” [14] It is necessary first to listen and then to try to chant the visions or the auditory images related by the voice of the ská pastora plant. This synesthetic process combines visual and hearing experiences with speaking.

Divination is closely associated with ská pastora. Salvia divinorum, its botanical name, can be translated as “sage of the diviners,” reflecting this long association. Divinatory uses for ská pastora are also found in healing rituals. The chotaj chinej healers and their patients are required to be attentive to the “voice of the leaf”—in Spanish, “la voz de la hoja” —that will make understandable the revelations that occur during the visionary experiences engendered by ská pastora. A chotaj chinej will transform visions into songs; through these songs, the patients will know the cause of their illnesses.

Mazatec divination using ská pastora is not limited to healing rituals; it can be used quite broadly to gather information. “When it is a question of a theft or a finding a thing that is lost, a curandero (curer, folk healer) listens to what is said by the man who has consumed the Salvia divinorum plant, and the facts about the theft or the thing lost are disclosed.” [15]

6. Implication

Ská pastora’s biological effects on humans pose problems for psychedelic research. Its principal psychedelic chemical cannot account for its visually oriented effects.

Salvia divinorum’s psychedelic principle is the chemical salvinorin A, which operates differently from other psychedelics. Salvinorin A is an active chemical substance that works through the kappa-opioid receptors in the brain instead of working through the serotonin 5HT2a neuroreceptors commonly associated with psychedelics such as Psilocybe mushrooms, peyote, ayahuasca, or LSD. The presence of salvinorin A in ská pastora creates a range of potential therapeutic properties for antidepressant, analgesic, and drug-abuse attenuation effects due to salvinorin A’s dopamine-release inhibitory capacity. [16] But these kappa-receptors being affected cannot account for the visual effects of ská pastora, requiring further research, mainly into the ways it activates neural networks; its visual effects must have further causes than salvinorin A. [17]

The most well-known cultural use of ská pastora is divination for healing purposes, but creative and aesthetic uses are also registered among Mazatec visionary artists, who reinterpret their ancient cultural heritage through a visual language that broadens the scope of ská pastora’s symbolism and cultural applications. Visual experiences are why ská pastora is ritually used as a source of knowledge. That knowledge is not a series of hallucinations. Mazatecs use ská pastora to achieve specific insights, not to undergo flights of illusion.

References

[1] Wasson, Robert Gordon. “A New Mexican Psychotropic Drug from the Mint Family.” Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University 20, no.3 (1962): 79. https://doi.org/10.5962/p.168538

[2] Personal Communication, Asunción Alvarado, June 26, 2025.

[3] Schultes, Richard Evans, Albert Hofmann and Christian Rätsch. Plants of the Gods. Their Sacred, Healing and Hallucinogenic Powers. (Healing Arts Press, 1992), 164.

[4] Da-Costa, Brito, Machado, Andreia, Dias-da-Silva, Diana, Gomes, Nelson G.M., Dinis-Oliveira, Ricardo Jorge, and Madureira-Carvalho, Aurea. “Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Salvinorin A and Salvia Divinorum: Clinical and Forensic Aspects.” Pharmaceuticals 14, no. 2; (2021): 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14020116.

[5] Casselman, Ivan, Catherine J Nock, Hans Wohlmuth, Robert P Weatherby, and Michael Heinrich. “From Local to Global—Fifty Years of Research on Salvia Divinorum.” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 151, no. 2, (2014): 769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2013.11.032.

[6] Schultes, Richard Evans, Albert Hofmann and Christian Rätsch. Plants of the Gods.Their Sacred, Healing and Hallucinogenic Powers. (Healing Arts Press, 1992), 164-165.

[7] De la Garza, Mercedes. Sueño y éxtasis en el mundo náhuatl y maya. (Fondo de Cultura Económica-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2012), 93.

[8] Díaz, José Luis. “Salvia divinorum. A Psychopharmacological Riddle and a Mind-Body Prospect.” Current Drug Abuse Review 6 (2013): 46.

[9] Aguirre Beltrán, Gonzalo. Medicina y Magia. El proceso de aculturación en la estructura colonial. (Instituto Nacional Indigenista-Secretaria de Educación Pública 1963), 138.

[10] Aguirre Beltrán, Gonzalo. Medicina y Magia. El proceso de aculturación en la estructura colonial. (Instituto Nacional Indigenista-Secretaria de Educación Pública 1963), 138.

[11] Johnson, Jean Basset. “The elements of Mazatec witchcraft.” Göteborgs Etnografiska Museum. Etnologiska Studier, vol. 9, (1939): 134.

[12] Maqueda, Ana Elda. “The Use of Salvia divinorum from a Mazatec Perspective.” In: Labate, Beatriz; Cavnar, Clancy. (Eds.), Plant Medicines, Healing and Psychedelic Science. Cultural Perspectives. Springer (2018), pp. 58-60. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-76720-8

[13] Estrada, Álvaro. Maria Sabina, Her Life and Chants. (Ross-Erikson, 1981), 83.

[14] Díaz, José Luis. “Salvia divinorum. A Psychopharmacological Riddle and a Mind-Body Prospect.” Current Drug Abuse Review 6. (2013): 43.

[15] Wasson, Robert Gordon. “A New Mexican Psychotropic Drug from the Mint Family.” Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University 20, no.3 (1962): 81 https://doi.org/10.5962/p.168538

[16] Díaz, José Luis. “Salvia divinorum. A Psychopharmacological Riddle and a Mind-Body Prospect.” Current Drugs Abuse Review 6. (2013): 50.

[17] Díaz, José Luis. “Salvia divinorum. A Psychopharmacological Riddle and a Mind-Body Prospect.” Current Drugs Abuse Review 6. (2013): 51.

[18] Schultes, Richard Evans. “Iconography of New World Plant Hallucinogens.” Arnoldia. 1981 Vol. 41. No. 3May-June (1981): 106.

Image 1. Birth of the Rainbow and the Shepherdess Mother (2023) by Asunción Alvarado.

Image 2. Leaves and flowers of Ska Pastora (Salvia divinorum ). [4]

Image 3. Map depicting in blue where Ska Pastora naturally grows, an area including Mazatec and Chinantec territories. [5]

Image 4. Illustration of Salvia divinorum. [18]