Xi´i Ndoto, Psilocybe mexicana

Codex Yuta Tnoho or Codex Vindobonensis mexicanus 1 (Sixteenth Century), Inquisition Records

Mixtec culture

1. Name

Psilocybe mexicana is a mushroom (Image 3) that grows in the State of Oaxaca and throughout Central Mexico; Psilocybe is a genus of mushrooms, some of which contain the psychoactive chemicals psilocybin and psilocin. Psilocybe mexicana is used for ritual and therapeutic purposes by many Indigenous Mesoamerican peoples: Chatins, Mazatecs, Mixes, Nahuas, Zapotecs, and Mixtecs.[1] Psilocybe mexicana mushrooms have a range of Indigenous names depending on the context in which they are used.

In Ñuu savi, the Mixtec language spoken in Oaxaca and its environs, the generic term for mushroom is jihi or xi´i.[2] One Ñuu savi-language term for visionary mushrooms is xi´i ndoto, which can be translated as “the fungus that awakens.”[3] In Nahua culture, Psilocybe mexicana is known as teonanacatl, “Flesh of the gods” [4], a term compounding the word teotl, meaning “god,” and the word nanácatl, meaning “fungus” or “flesh.” In Mixe/Ayuuk language, Psilocybe mexicana’s name is pi:pti, or pi:pta, meaning “resembles a thread”.[5]

Several species of Psilocybe mushrooms grow in territories occupied by Mesoamerican cultures, and different cultural uses correspond to different Psilocybe species. Three species for sacramental use by Ñuu savi (Mixtec) people are Psilocybe mexicana, Psilocybe caerulenscens, and Psilocybe zapotecorum.

2. Introduction and Artwork

The Codex Yuta Tnoho or Codex Vindobonensis Mexicanus 1 is a sixteenth-century pictographic manuscript created by Ñuu savi (Mixtec) people of contemporary Oaxaca, Guerrero, and Puebla regions of Mexico. The Codex portrays Ñuu savi cosmogony by depicting the creation of the universe before the First Dawn that consecrates corn, pulque (a fermented beverage), and visionary mushrooms, all essential crops for Ñuu savi people.[6] The Ñuu savi culture links rain, water, maize, and mushrooms to fertility; all four are represented in Plate 24 of the Codex. Image 1 details sacred entities and gods associated in consecration rituals in plate 24 of the Codex. Toponyms are depicted symbolically in the Codex—they can be recognized by Ñuu savi glyphs for “town.” Plate 24 also depicts dates—they can be recognized as colorful dots attached to a symbol by a line. The Codex’s pictographic language can be read starting from the bottom-right side, gradually ascending counterclockwise to the upper right corner, and continuing to the left side of the plate. The names of many deities in this image, such as Nine Wind or Lady Eleven Lizard, contain pictographic numbers that are easily recognized by Indigenous readers of the images. The interpretations below are enriched by the research of two scholars who are themselves Ñuu savi: Faustino Hernández Santiago and Gabina Aurora Pérez Jimenez.

To the center-right side is Nine Wind, who carries on his back a sacred entity named Lady Eleven Lizard, who holds four mushrooms on her headdress. Behind Nine Wind and Lady Eleven Lizard is Lady Four Lizard, who also holds four mushrooms on her headdress. Lady Eleven Lizard and Lady Four Lizard both symbolize the female spirit of the sacred mushrooms, and they both also display their own totemic animal or nagual, the Lizard, which is closely associated with fertility.

Nine Wind, Lady Eleven Lizard, and Lady Four Lizard are moving to the left towards the God of Rain and Thunderbolts located in front of a corn plant; he wears a turquoise mask with snake fangs. The Snake, whose shape and movements resemble lightning bolts, is this god’s totemic animal. In Mesoamerican cultures, the God of Rain and Thunderbolts is closely associated with sacred mushrooms, and the most powerful mushrooms in earth where lightning has struck.

The Ñuu savi scholar Faustino Hernandez Santiago explains that “The story begins on the banks of the Apoala River or Yuta Tnoho, with the meeting of two ñuhu (name the Mixtecs use for sacred beings even today), one red and the other golden. Then, there is a dialogue between two deities, a venerable old man and the hero of the Mixtecs people, 9-Wind or Coo Dzavui.”[7] The name of Coo Dzavui—Nine Wind, the god who carries Lady Eleven Lizard above—can be translated “Serpent of the Rain.” He has been compared to Quetzalcoatl, the feathered-serpent god of the Nahua Aztecs.

The god Nine Wind sings while he makes music using an instrument that scrapes a bone against a skull. Anders, Jansen, and Perez Jimenez explain that Nine Wind sings hymns, “scraping bones on a skull, while eight of the First Lords ate the mushrooms. Lord 7 Flower, seated on a jaguar skin cushion, was the leader of the group: he was crying in a trance.”[8] Lord Seven Flower has been compared to the Nahua god Piltzintecuhtli, “Young Lord,” the god of the rising son, healing, and visions. Lord Seven Flower, tears in his eyes and holding two mushrooms, is positioned in front of Nine Wind.

To the left of Lord Seven Flower and Nine Wind are deities participating in a cosmogonic ritual. Each deity carries two mushrooms in their hands, reflecting Mesoamericans’ sacred views about duality. Anders, Jansen, and Perez Jimenez Identify the following deities: “[…] in front of him participated Lord 2 Dog, the Elder Priest, Lord 1 Death, Sun [Macuilxóchitl], Lord 4 Movement, Nuhu with Jaguar Mouth, Long Curls and Crown of Knotted Paper, Lady 9 Reed, Quechquemitl of Jade, Lady 1 Eagle, the Grandmother, Lady 9 Grass, Lady of Death [Ciuacoatl], Lady 5 Flint, Flower of Corn. They had a great vision.”[9]

Limited space prevents the examination here of historical genealogies of Ñuu savi rulers as depicted on Plate 24 of the Codex Yuta Tnoho or Codex Vindobonensis mexicanus 1.

3. Geography and Context

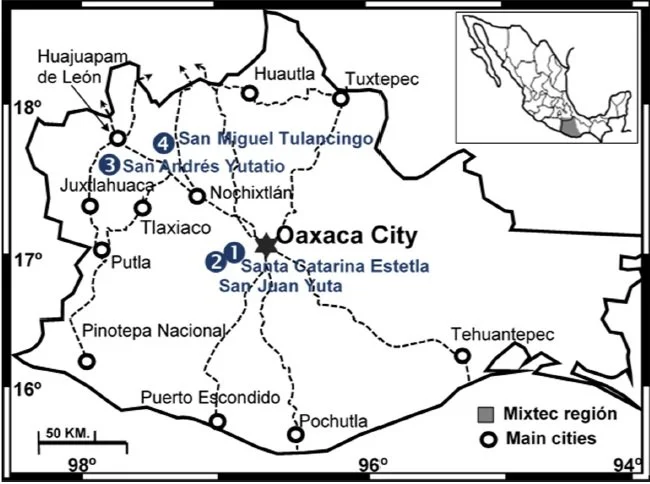

Xi´i ndoto mushrooms (Image 3) grow in several regions of Oaxaca, Mexico. Psilocybe mexicana grows in subtropical regions below 2800 meters of elevation, though they do not grow there exclusively. “Psilocybe mexicana […] seems to have had its origin from tropical terricolous species such as from the evergreen tropical forests, which have small spores and brown cystidia.”[10] Psilocybe mushrooms in Mexico can be classified into three groups corresponding to different geographical ecological zones, and Xi´i ndoto belongs to the group “encompassing the great majority of hallucinogenic species in Mexico, [that] is found in the intermediate zones where a moist, subtropical climate and hilly terrain give rise to mesophytic cloud forest at elevations of 1,000-1,600 m[eters].”[11]

4. Primary Sources

Mushrooms are 80% water, making analysis from material remains of xi´i ndoto impossible; however, an abundant corpus of sculptures, codices, and ritual paraphernalia suggest xi´i ndoto’s early use.

The Codex Yuta Tnoho or Codex Vindobonensis Mexicanus 1 dates from pre-Hispanic times in the early sixteenth-century and depicts ancient rituals using visionary mushrooms and also depicts a range of cosmogonic symbols and narratives. The Codex refers to the Ñuu savi (Mixtec) place of origin at the sacred tree of Apoala and the ritual that took place before the First Dawn.[13] It also contains toponyms that continue to be inhabited by contemporary Ñuu savi people.

Inquisition archives on the topic of Indigenous rulers of Yanhuitlan, Oaxaca, in the Ñuu savi region, describe a range of sacred mushrooms’ sacramental uses. Robert Gordon Wasson explains that “In proceedings before a Spanish scribe and notary, three Indians notables gave testimony concerning their ostentatious worship of the gods of the old religion. As they have been baptised, they were of course apostates. The principal Indian gave his testimony in Mixtec. It seems that he had taken inebriating mushrooms to invoke divine help in various circumstances.”[14]

Ethnographic research and the interpretations by Ñuu savi scholars reveal xi´i ndoto’s cultural uses—sacramental, therapeutic, and divinatory—and nuance the symbolism of sacred mushrooms by exploring cultural features of the entheogenic experience, especially xi´i ndoto facilitating encounters with wisdom and gaining wisdom. While “the use of [specific] hallucinogenic mushrooms in the communities under study was not reported . . . informants mentioned that in the San Antonio Huitepec municipality south of the Santa Catarina Estetla and San Juan Yuta Communities healers and shamans use mushrooms for divination or healing purposes.” [15] Xi´i ndoto mushrooms still grow in this territory, but knowledge about their cultural use is disappearing.

5. Interpretation

In Ñuu savi (Mixtec) worldview, xi´i ndoto mushrooms have the quality of being animated, an aspect of their personhood. They are an integral part of the sacred landscape that cannot be detached from the territory where they grow. “The mushroom has the quality of being animate. There is a conversation between the mushroom and the one who takes it. The fungus knows much, and thus is able to foretell. As the mushroom itself foretells, the proposition of ingesting it, as an intention, is what put one into contact with the spirit of the mushroom. Insofar as the mushroom knows of deeds and activities that man cannot know without its aid, the fungus represents the extra-human world. In itself it contains a supernatural or sacred force related to wisdom.” [16] Due to xi´i ndotos’ visionary properties, images depicting sacred entities and supernatural beings likely emerged from visions or dreams during entheogenic experiences.

The spirit of the xi´i ndoto has a feminine character among the Ñuu savi. In ritual preparations, a girl is in charge of collecting and preparing xi´i ndoto mushrooms. "The meaning of the mode of preparation increases its importance taking into account the kind of person who grinds it, for it must necessarily be a girl, which is also a necessary and unique element in the Mixtec pattern. Undoubtedly, we are in the presence of a belief about the essential quality of the mushroom expressed socially through the kind of person representing complete purity: the girl. The reverent attitude shown toward the mushroom its only parallel at the other end of the social scale in respect for the elders." [17]

Xi´i ndoto have been hypothesized to be connected to art, especially painting and writing, including the painting/writing of codices like the Codex Yuta Tnoho or Codex Vindobonensis Mexicanus 1. During fieldwork undertaken in Necaxa, a Nahua region in the Mexican State of Puebla, the mycologist Gaston Guzmán registered the name teotlaquilnanacatl—its correct spelling is teotlacuilnanacatl—for Psilocybe mushrooms, and that name can be translated as “an Aztec word that probably means “mushrooms of the gods” or “divine one who paints or writes,” from teo = god, tlaquilo or tlacuilo (= painter or writer) and nanacatl = mushroom.” [18] Another possible translation of the Nahuatl-language term teotlacuilnanacatl is the “mushroom of the sacred writing,” linking the use of Psilocybe mushrooms with the creative process in painting and writing. This is only a hypothesis, and all codices should not be considered composed under the influence of Psilocybe mushrooms. Writing is related to wisdom. Native Mesoamerican people’s association of psilocybe mushrooms with writing affirms that Psilocybe mushrooms are considered a source of wisdom and truth.

The entheogenic experiences brought about by Psilocybe mushrooms are not a series of hallucinations, as Western prohibitionist policies continue to depict them. The term xi´i ndoto means the “fungus that awakens,” which denies the incorrect assumption that the entheogenic experience is an escape from reality. The goal of xi´i ndoto and its use is to awaken a person. Xi´i ndoto extends consciousness in the search for wisdom to solve an illness or address a problem.

6. Implications

Nowadays, cultural usage of xi´i ndoto by Ñuu savi (Mixtec) is threatened by the enduring effects of colonization and the prevailing criminalization and stigmatization resulting from lack of information and because general audiences and authorities still consider Psilocybe mushrooms to be a drug. Mexican Law contains an exception to prohibitions for the sacramental use of Psilocybe mushrooms by Indigenous peoples; unfortunately, many communities are not aware of this legal exception. Criminalization and lack of recognition erase cultural heritage.

Xi´i ndoto mushrooms enable communication between humans and ancestors as well as sacred and more-than-human beings, including rain deities and guardians of hills, caves, springs, rivers, lagoons, or forests. Sacred entities, including xi´i ndoto, are identified to be natural forces, and they are recognized and respected as persons. Personhood is a cultural feature that understands the world in human terms.

The process of personhood, a dialogical process of communication through chants and prayers and entering reciprocal relationship, has ethical consequences. Dealing with a person is not the same as dealing with an object or substance— which is how many contemporary psychedelic activists and clinical scientists widely perceive Psilocybe—or as a drug—which is how prohibitionists invariably perceive Psilocybe.

Among Ñuu savi, xi´i ndoto have a range of uses and purposes. Therapeutic uses: It is stated that the mushroom has healing power. Xi´i ndoto discovers the causes of diseases and prescribes the appropriate cure. Divinatory uses: Xi´i ndoto is an agent who forecasts the future and talks about the past. Ritual uses: Xi´i ndoto’s preparation is striking: The Mixtec pattern for preparing xi´i ndoto consists of grinding it with water in the metate, a stone base for grinding grains, before consuming it. In other cultures, such as the Mazatec, it is customary to eat the mushroom whole or shredded, but not ground. Creative uses: The hypothesis that some mushrooms were used for creative purposes—including to paint or to write codices—sheds light on an overlooked vein of research that explores the rich and diverse creative and aesthetic uses of sacred plants and fungi by Native Mesoamerican peoples.

References

[1] Guzmán, Gastón. "Hallucinogenic Mushrooms in Mexico: An Overview." Economic Botany 62, no. 3 (2008): 404-412.

[2] Hernández Santiago, Faustino, Jesús Pérez Moreno, Beatriz Xoconostle Cázares, Juan José Almaraz Suárez, Enrique Ojeda Trejo, Gerardo Mata Montes de Oca, and Irma Díaz Aguilar. "Traditional Knowledge and Use of Wild Mushrooms by Mixtecs or Ñuu Savi, the People of the Rain, from Southeastern Mexico." Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 12, no. 1 (2016): 35.

[3] Hernández Santiago, Faustino, Magdalena Martínez Reyes, Jesús Pérez Moreno, and Gerardo Mata. "Pictographic Representation of the First Dawn and Its Association with Entheogenic Mushrooms in a 16th Century Mixtec Mesoamerican Codex." Scientia Fungorum 46 (2018). https://doi.org/10.33885/sf.2017.46.1173.

[4] Guzmán, Gastón. "Hallucinogenic Mushrooms in Mexico: An Overview." Economic Botany 62, no. 3 (2008): 404-412.

[5] Hoogshagen, Searle. "Notes on the Sacred (Narcotic) Mushrooms from Coatlan Oaxaca, Mexico." Oklahoma Anthropological Society Bulletin 7 (1959): 71-74.

[6] Anders, Ferdinand, M.E.R.G.N. Jansen, and G.A. Pérez Jiménez. Origen e Historia de los Reyes Mixtecos: Libro Explicativo del Llamado Códice Vindobonensis. Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1992; Hernández Santiago, Faustino, Magdalena Martínez Reyes, Jesús Pérez Moreno, and Gerardo Mata. "Pictographic Representation of the First Dawn and Its Association with Entheogenic Mushrooms in a 16th Century Mixtec Mesoamerican Codex." Scientia Fungorum 46 (2018).

[7] Hernández Santiago, Faustino, Magdalena Martínez Reyes, Jesús Pérez Moreno, and Gerardo Mata. "Pictographic Representation of the First Dawn and Its Association with Entheogenic Mushrooms in a 16th Century Mixtec Mesoamerican Codex." Scientia Fungorum 46 (2018): 26.

[8] Anders, Ferdinand, M.E.R.G.N. Jansen, and G.A. Pérez Jiménez. Origen e Historia de los Reyes Mixtecos: Libro Explicativo del Llamado Códice Vindobonensis. Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1992.

[9] Anders, Ferdinand, M.E.R.G.N. Jansen, and G.A. Pérez Jiménez. Origen e Historia de los Reyes Mixtecos: Libro Explicativo del Llamado Códice Vindobonensis. Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1992.

[10] Guzmán, Gastón. "Variation, Distribution, Ethnomycological Data and Relationships of Psilocybe aztecorum, a Mexican Hallucinogenic Mushroom." Mycologia 70, no. 2 (1978): 385-396.

[11] Guzmán, Gastón. "Hallucinogenic Mushrooms in Mexico: An Overview." Economic Botany 62, no. 3 (2008): 404-412.

[12] Hernández Santiago, Faustino, Magdalena Martínez Reyes, Jesús Pérez Moreno, and Gerardo Mata. "Pictographic Representation of the First Dawn and Its Association with Entheogenic Mushrooms in a 16th Century Mixtec Mesoamerican Codex." Scientia Fungorum 46 (2018): 21.

[13] Caso, Alfonso. "Representaciones de Hongos en los Códices." Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl 4 (1963): 27-36.

[14] Wasson, Robert Gordon. The Wondrous Mushroom: Mycolatry in Mesoamerica. McGraw-Hill Books, 1980.

[15] Hernández Santiago, Faustino, Jesús Pérez Moreno, Beatriz Xoconostle Cázares, Juan José Almaraz Suárez, Enrique Ojeda Trejo, Gerardo Mata Montes de Oca, and Irma Díaz Aguilar. "Traditional Knowledge and Use of Wild Mushrooms by Mixtecs or Ñuu Savi, the People of the Rain, from Southeastern Mexico." Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 12, no. 1 (2016): 35.

[16] Ravicz, Robert. "The Mixtec in a Comparative Study of Hallucinogenic Mushrooms." In The Sacred Mushrooms of Mexico, edited by Brian P. Akers, 39-60. University Press of America, 2007.

[17] Ravicz, Robert. "The Mixtec in a Comparative Study of Hallucinogenic Mushrooms." In The Sacred Mushrooms of Mexico, edited by Brian P. Akers, 39-60. University Press of America, 2007.

[18] Guzmán, Gastón. "Nueva Localidad de Importancia Etnomicológica de los Hongos Neurotrópicos Mexicanos." Ciencia, México 20 (1960): 85-88.

Image 1. Codex Yuta Tnoho or Codex Vindobonensis Mexicanus 1, Plate 24.

Image 2. Map of the Ñuu savi (Mixtec) region. [12]

Image 3. Psilocybe mexicana observed by Alan Rockefeller on iNaturalist. https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/182283461