1. Name

Ayahuasca and yagé are psychedelic brews made from plant blends, some of which contain naturally occurring dimethyltryptamine (DMT), a psychedelic chemical compound. Ayahuasca uses the Psychotria viridis shrub (chacruna, in the Quechua language), while yagé incorporates the Diplopterys cabrerana (chagropanga) plant. Both plant sources of DMT are part of a pharmacological complex; both brews are synergies of DMT sources with ß-carbolines and harmala alkaloids. Unlike synthesized DMT that is smoked, ayahuasca and yagé are liquid preparations consumed orally as a tea. In addition to the Psychotria viridis shrub, ayahuasca contains the Banisteriopsis caapi vine, a source of β-carboline alkaloids—monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI) that include harmine, harmaline, and tetrahydroharmine. [1] MAOIs inhibit the natural production of monoamine oxidase in the body that breaks down the psychedelic alkaloid dimethyltriptamine (DMT). [2]

Ayahuasca and yagé are the most common names and recipes for this DMT brew today, but these are not necessarily the only ones or the most ancient. According to Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff, the brew has many Indigenous names: “Among the Eastern Tukano people of the Vaupes, this brew is called caapi, or gahpi or kahpi […] among the Cubeo, it is called mihi. […] Also in the lowlands of Panama and Colombia, it is called ddpa among the Noanama, and among the Embera of Northwest Colombia and Southeastern Panama, it is called pilde. […] Among residents of the Montaña regions of Peru and Ecuador, in the Quechua language […] it is known by the term ayahuasca.” [3] The wide diversity of names exemplifies the cultural significance of these sacred plants for different Native American traditions across South America.

2. Introduction and Artwork

The cosmogony of the Tukano people in the Northwest Amazon describes the first inhabitants of the Earth descending from the Milky Way, bringing yagé with them from the stars; thereby, yagé is an essential part of their cosmogony (Image 1). In one of these cosmogonies, a large Anaconda canoe, shaped like the sacred serpent, descends from the River of Stars and transports a primordial man and woman along with three plants: the foodstuff manioc (or yuca), the psychoactive coca plant, and the psychedelic caapi or yagé. [4]

Other Tukano cosmogonic stories describe a Yagé woman, the Daughter of the Sun, giving birth to a luminous child, who himself is Yagé, born in a blinding flash of light. The Yagé woman walks to the House of Waters, her place of origin. “She had looked at the brilliance of the sun and had become impregnated through the eye . . . And when she gave birth, there was another flash of light because the infant, being the Son of the Sun, shone brightly in the darkness of those primeval times. The child was made of light; it was human, but it was light, it was Yagé.” [5] Therefore,Yagé is a divine gift from Father Sun, conveyed to humans by his daughter, the Yagé woman, through her son, who is himself Yagé.

Tukano cosmogony sets out another primordial deity, the Master of Animals (Vahí-mansë), whose daughter conveys the contents of the psychedelic brew to humans. Usually depicted as a small man or as a red dwarf, the Master of Animals is called “Vahí-mansë” (Image 2), which literally means “fish master.” He holds dominion over the hunt and fertility, and he is the owner and guardian of magical herbs that provide luck to hunters, enabling the success of the hunt. [7] The daughter of the Master of the Animals (Vahí-mansë mangó) is the “owner” of yagé, the sacred brew with psychedelic-related properties, meaning that rituals and offerings associated with yagé should be devoted to her. [8]

3. Geography and Context

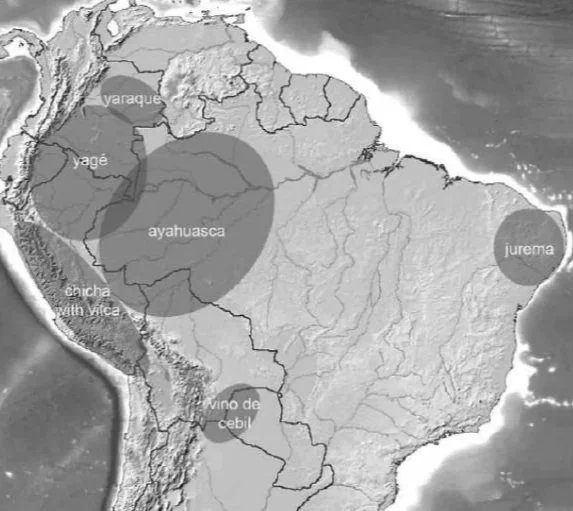

The two brews, ayahuasca and yagé, can be distinguished by their geographic context. Ayahuasca is generally brewed in Brazil and Peru, and yagé is usually brewed in Colombia and Ecuador. The ayahuasca brew includes chunks of the Banisteriopsis caapi vine and the leaves of the Psychotria viridis (in the Quechua language, chacruna).[9] For yagé brew, the basic mixture consists of Banisteriopsis caapi vine and Diplopterys cabrerana leaves (chagropanga, ocoyagé). Both the Psychotria viridis (chacruna) and the Diplopterys cabrerana (chagropanga) are sources of DMT. While the chemical compounds in the two brews are essentially the same, scholars emphasize that there is significant nuance across Indigenous taxonomies and knowledge; such nuance is not recognized by Western science.

Approximately 100 species from 40 plant families are reported as ayahuasca and yagé admixtures, which are part of their combined ingredients; many of these admixtures are themselves psychoactive plants, contributing to the psychedelic effects of the brewed Banisteriopsis caapi vine and either Psychotria viridis or Diplopterys cabrerana leaves. There is no one specific blend considered the quintessential or original brew, just as there is no single quintessential or original name for the brew.

4. Primary Sources

The earliest historical documentation of ayahuasca appears to be reports by José Chantre y Herrera, who compiled a history of Jesuit activity from 1637 to 1767 in the Marañon River area, a source for the Amazon River in what is now Peru and Ecuador. Chantre y Herrera includes a brief description of an ayahuasca ritual that clearly references the mixing of a liana, the Spanish word for “vine”—presumably Banisteriopsis caapi—with other plants. “The diviner hangs his bed in the middle or sets up his stage on platform and places a hellish concoction next to it, called ayahuasca, which singularly effective in rendering one unconscious. A decoction is made from vines or bitter herbs, which must be boiled until it becomes very thick. As it is so strong then even a small amount can cloud the judgment, the amount needed is not much, and fits into two small cups.” [11] The negative colonial gaze is well displayed in Chantre y Herrera’s expressions, such as “hellish concoction” or “rendering one unconsciousness.”

5. Interpretation

Tukanos’ visual representations of caapi (ayahuasca/yajé) consist mainly of two different categories of art, represented in graphic symbols that align with the effects of the potent brew upon those who drink it. [14] Neither category is a naturalistic visual depiction of the Tukanos’ surrounding environment.

(1) The Tukano people create geometrical patterns in paintings that adorn artifacts, appear throughout their material culture, and are displayed in communal houses called “malocas” (Image 1). Some researchers associate these geometrical patterns with entheogenic or psychedelic experience, especially phosphenes [15], visual sensations of light when no actual light is present, and widespread experiences of luminosity.

(2) Tukano people also draw figurative designs to depict their worldview, including representations of sacred and mythological characters, [16] usually in anthropomorphic or zoomorphic forms (Image 2), which are sometimes featured alongside or within the geometrical patterns.

Tukano graphic symbols are a system of communication that represents a collective knowledge embedded in iconography and a form of grammar in geometrical patterns. Geometrical patterns acquired a practical function in Tukano culture; they are graphic symbols or signs that express major tenets of behavior. [17]

Graphic, symbolic messages remind those who view them to practice moderation in hunting and fishing, in eating, in needlessly destroying the environment, in fighting, and in population increase. For instance, the Master of the Animals, Vahí-mansë above, sends illness due to ritual transgressions and lack of reverence, requiring negotiations by entranced medicine men (payé) to resolve his punishments. On the other hand, the Sun Father is a medicine man (payé). He is the ancestor of contemporary payés and the origin of their powers, for he created “Vihó-mahse, the Being of Vihó, the hallucinogenic powder, and ordered him to serve as an intermediary so that through hallucinations people could put themselves in contact with all the other supernatural beings.” [18] Within sacred narratives, the Sun Father also brought in his navel a psychoactive snuff (vihó) that contains the bark resin of trees from the Virola genus in the Myristicaceae family.

6. Implications

Due to rising interest in their therapeutic potential, today ayahuasca and yagé brews are well-known globally. The brews have been reinterpreted and distributed by a number of contemporary churches and religious movements in the West, such as Santo Daime and União do Vegetal churches. Ancient traditions surrounding the use of these psychedelic brews continue to be practiced by Indigenous communities, but their sacred narratives and rituals are frequently overlooked or misunderstood.

The sacred Tukano narratives presented above exemplify the rich Indigenous cosmologies around these psychedelic brews. The Sun Father’s role in the origins of yagé and the Master of Animals’ moral teachings against the overhunting and exploitation of nature demonstrate Indigenous moral teachings and the preservation of the natural environment. Above all, the Tukano cosmogony highlights that yagé is a divine gift.

References

[1] Naranjo, Claudio. “Psychotropic Properties of the Harmala Alkaloids.” In Ethopharmacological Research for Psychoactive Drugs: Proceedings of a Symposium held in San Francisco, California, edited by Daniel Efron (National Institute of Mental Health, 1967), 385.

[2] Santos, Beatriz Werneck Lopes, et al. “Biodiversity of β-Carboline Profile of Banisteriopsis caapi and Ayahuasca, a Plant and a Brew with Neuropharmacological Potential.” Plants 9, no. 7: 870 (2020): 2.

[3] Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. “The Cultural Context of an Aboriginal Hallucinogen: Banisteriopsis Caapi.” In Flesh of the Gods: The Ritual Use of Hallucinogens, edited by Peter Furst (Waveland Press, 1990 [1972]), 85.

[4] Torres, Constantino Manuel. “The Origins of the Ayahuasca/Yagé Concept: An Inquiry into the Synergy between Dimethyltryptamine and Beta-Carbolines.” In Ancient Psychoactive Substances, edited by Scott M. Fitzpatrick (University Press of Florida, 2018), 239.

[5] Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. Beyond the Milky Way: Hallucinatory Imagery of the Tukano Indians. (UCLA Latin American Center, 1978), 4.

[6] Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. Beyond the Milky Way: Hallucinatory Imagery of the Tukano Indians. (UCLA Latin American Center, 1978), 38.

[7] Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. Amazonian Cosmos: The Sexual and Religious Symbolism of the Tukano Indians. (University of Chicago Press, 1971), 80.

[8] Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. Amazonian Cosmos: The Sexual and Religious Symbolism of the Tukano Indians. (University of Chicago Press, 1971), 36.

[9] Torres, Constantino Manuel. “The Origins of the Ayahuasca/Yagé Concept: An Inquiry into the Synergy between Dimethyltryptamine and Beta-Carbolines.” In Ancient Psychoactive Substances, edited by Scott M. Fitzpatrick (University Press of Florida, 2018), 236-237.

[10] Torres, Constantino Manuel. “The Origins of the Ayahuasca/Yagé Concept: An Inquiry into the Synergy between Dimethyltryptamine and Beta-Carbolines.” In Ancient Psychoactive Substances, edited by Scott M. Fitzpatrick (University Press of Florida, 2018), 235.

[11] Chantre y Herrera, José. Historia de las misiones de la Compañía de Jesús en el Marañón español. (Imprenta de A. Avrial, 1901), 80.

[12] Schultes, Richard Evans. “Iconography of New World Plant Hallucinogens.” Arnoldia 41, no. 3 (1981): 92.

[13] Schultes, Richard Evans. “Iconography of New World Plant Hallucinogens.” Arnoldia 41, no. 3 (1981): 120.

[14] Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. Beyond the Milky Way: Hallucinatory Imagery of the Tukano Indians. (UCLA Latin American Center, 1978), 149.

[15] Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. Beyond the Milky Way: Hallucinatory Imagery of the Tukano Indians. (UCLA Latin American Center, 1978), 43.

[16] Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. Beyond the Milky Way: Hallucinatory Imagery of the Tukano Indians. (UCLA Latin American Center, 1978), 47.

[17] Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. Beyond the Milky Way: Hallucinatory Imagery of the Tukano Indians. (UCLA Latin American Center, 1978), 152.

[18] Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. Amazonian Cosmos: The Sexual and Religious Symbolism of the Tukano Indians. (University of Chicago Press, 1971), 27.

Ayahuasca / Yagé

Tukano Culture and Cosmogony

Various South American Native Cultures

Image 1. A Star Shaped Design. [6]

Image 2. The Master of Animals. Painted Taibano maloca. [6]

Image 3. Map with geographical distribution of ayahuasca and yagé, among other substances containing DMT.[10]

Image 4. Banisteriopsis caapi. Observation by Alan Rockefeller, documented on iNaturalist. inaturalist.org/observations/261857865

Image 5. Diplopterys cabrerana. Observation by Carlo Brescia, documented on iNaturalist. inaturalist.org/observations/101744405

Image 6. Banisteriopsis Caapi. Morton. Illustrated in Hammerman in Bull. Appl. Bot. Leningrad 22, iv (1929) 192.[12]

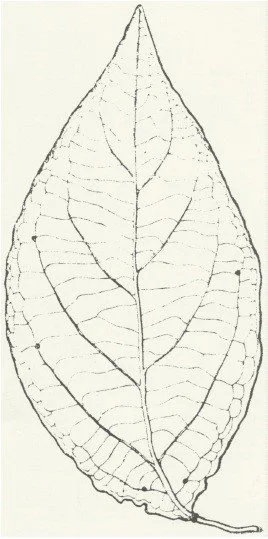

Image 7. Psychotria viridis. The earliest drawing of Psychotria viridis Ruiz et Pavón. Illustrated in Ruiz and Pavón, Fl. Peruv. Et Chil. 2 (1799) t. 210, fig. b.[13]