1. Name

Known in English as peyote, the names of this sacred cactus—peyotl, hikuri, jikuli, or jiculí—come from languages belonging to the Uto-Aztecan language family, which includes languages spoken throughout Aridoamerica, Mesoamerica and the Western United States. This entry favors the Nahuatl name “peyotl.”

Anthropologist and peyotl scholar Stacy B. Schaefer explains, “Since peyote first came under scrutiny of western botanists and psychopharmacologists, it has gone through a series of name changes, until science settled in Lophophora for the genus and williamsii and diffusa for the two species of peyote that have been positively identified.” [1]

The Nahuatl language name “peyotl” can be translated as “silk cocoon.” The Huichol language name “hikuri” can be translated as “mirror” and “moon.” The Wixárika people, also known as Huichol, are an Indigenous people in Western and Northwestern Mexico, primarily in the Sierra Madre Occidental mountain range. “Jikuli” or “Jiculí” are names for peyote used by the Raramuri or the Tarahumara in the Mexican state of Chihuahua, by the Cora in Nayarit, and by the Tepehuan in Durango. Historians have registered the sacramental use of peyotl by the Lipan Apaches in the plains of Northern Mexico and Texas and by the Teochichimecas, a nomadic people. All these Indigenous peoples maintain sacramental use of peyotl cactus.

2. Introduction and Artwork

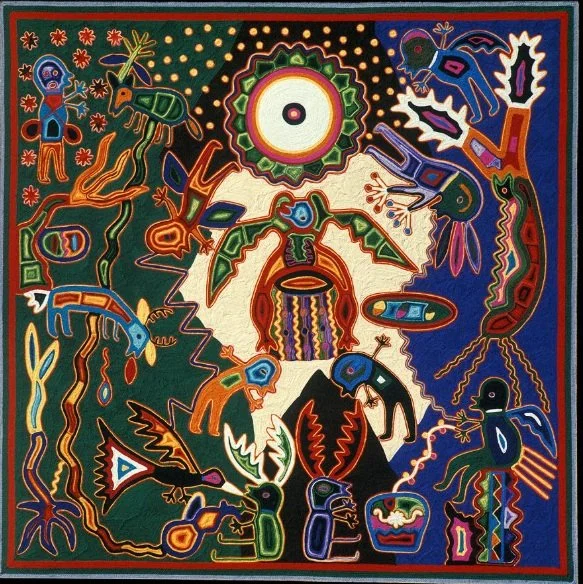

Featured in Image 1, the visionary artist José Benítez Sánchez’s yarn painting titled Kauyumarie’s Nierika illustrates a Wixárika (Huichol) cosmogony tale in which the sacred forces emerge from the underworld and then come to the Earth. The radiant disk featured is a nierika, which is peyotl (peyote) and is also a mirror, a cactus, a blue path of the sacred Kauyumarie deer—each peyotl button resembles and represents these ideas.

The Blue Deer named Kauyumarie, meaning “Our Old Brother Deer,” finds the nierika, the luminous circle that is a gateway to the spirit world, a common element in Wixárika (Huichol) art. His nierika unifies the spirit of physical beings and the spirit worlds. Beings come to life through the nierika. The lines stretching out from the center on physical peyotl buttons are thought to resemble the cosmological paths of the sacred Kauyumarie Blue Deer in this sacred narrative.

Below the nierika, Tatéi Werika Wimari, whose name means “Our Mother Eagle,” opens her wings and bows her head to listen to Kauyumarie, who sits on a rock below and to the right of her. Kauyumarie’s words descend on a thread and into a vessel, transforming his speech into vital energy depicted as a white flower. Above Kauyumarie, in the form of a serpent with deer horns, “Spirit of the Rain” gives life to the gods who stretch around these images as they spread across the earth. [2]

3. Geographical distribution

Peyotl (peyote) grows mainly in Northern Mexico and Southern Texas desert regions in special ecological zones with the right soil for the cactuses to thrive. Lophophora williamsi, the botanical name for peyotl, is native to the high desert region of San Luis Potosí, which the Wixárika (Huichol) people call Wirikuta, and is also native to parts of the Mexican states of Zacatecas and Coahuila and to the South Texas plains along the Lower Río Grande. Lophophora diffusa, a cactus of the same family, is only observed growing in a small desert zone in the Mexican State of Queretaro. [3]

Recent archeological research has discovered seeds and peyotl buttons, along with petroglyphs depicting the peyotl cactuses, in the Northeastern Mexican state of Nuevo León, an understudied region [4]. Archeologists in the “Prehistory and Historical Archaeology of Northeastern Mexico” project found peyotl seeds in Villaldama, an ancient archeological site in Nuevo León that dates from at least 12,000 BP. (Used in carbon dating, BP is a dating designation meaning “before the present,” before the year 1950. Archaeologists use this term and the more conventional BCE and CE depending upon the evidence they interpret.) There are no data regarding radiocarbon tests on the seeds or buttons, but other artifacts there, such as flint arrows, have been carbon-dated to 6000 BP. As part of a hearth, two molars from the mouth of an extinct American equine date to almost 11,000 years BP. [5]

4. Primary Sources and Evidence

Archaeological evidence locates peyotl (peyote) buttons in prehistoric sites throughout what is now Texas and Northern Mexico. Analysis of rock art, ceramic vessels, iconography, and colonial sources reveals a long history of peyotl use in the Americas.

Discus-shaped, dried peyotl buttons were discovered near ancient rock art in the Shumla caves on the Texas side of the Rio Grande River. [7] These preserved buttons are radiocarbon dated to approximately 4,000 years before the common era (BCE), and they still contain mescaline at a concentration of around two percent. [8] Several cave and rock-shelter sites in Texas contain preserved peyotl whose radiocarbon dates range between 5000 and 5700 BCE. [9]

In West Central Coahuila, Mexico, a dried, preserved peyotl button that was part of a necklace was found in the Mayran mortuary complex, a multiple-interment burial cave, suggesting the necklace was part of funeral offerings. This peyotl button is dated between 810 and 1070 CE. Analysis to identify its alkaloids reveals mescaline, the psychedelic principle in peyotl, but also chemical compounds including lophophorine, anhalonine, pellotine, and anhalonidine that all had an entourage effect when consumed. Lithic and perishable items were also found at the site. [10]

Recent archeological excavations of the La Morita II cave in Nuevo Leon, Mexico, revealed an array of rock art manifestations carbon-dated to be from 6000 BP (before the present). Archeologists conclude that the cave had mixed functions for daily life and as a funerary site. “This deduction is based on the location of spears and projectile points to 4500 BP; remains of objects made from perishable materials, such as fragments of cordage and basketry from 300 BP . . . Other elements that contextualize daily life in the cave were coprolites (dried feces) and seeds of cacti, such as peyote and three species of the region.” [11]

The sixteenth-century Florentine Codex, the seventeenth-century Parecer de Juan de Salcedo sobre el Peyote, and Inquisition trial records describe cultural uses of peyotl that include medicine and divination as well as ritual and sacramental uses. Book X, Chapter XXIX, of the Florentine Codex provides information regarding the knowledge developed by the Teochichimeca, nomadic people who lived in northern Mexico: “And they knew the qualities, the essence, of herbs, of roots. The so-called peyote was their discovery. These, when they ate peyote, esteemed it above wine or mushrooms. They assembled together somewhere in the desert; they came together; there they danced, they sang all night, all day. And on the morrow, once more they assembled together. They wept; they wept exceedingly. They said [thus] eyes were washed; thus they cleansed their eyes”. [12] The Florentine Codex Book XI, Chapter VII, further describes peyotl’s visionary properties.

5. Interpretation

Considering the long history and wide array of Indigenous traditions, there is likely no single cult or homogenous ritual or ritual system for sacramental use of peyotl (peyote). Ancient rituals have been registered for a number of Northern Mexico Indigenous peoples: Teochichimecas, Wixáricas, Coras, Raramuris, and Lipan Apaches. Colonial sources, however, show a clash of cultural paradigms between Native American cosmologies and the Catholic Church.

According to the unpublished manuscript Parecer de Juan de Salcedo sobre el Peyote—written in 1619 by the rector of the Real y Pontificia Universidad and now held by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Library—since the First Apostolic meeting of 1524 in Mexico, the Church considered the sacramental use of peyotl to be an obstacle to evangelizing Indigenous peoples because peyotl rituals and peyotl lore resemble ancient rituals and worldviews predating Christianity in the New World. Peyotl and its sacramental use were officially banned by an inquisition edict in 1620, but 100 inquisition trial records document cultural uses of this sacred cactus during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

In the nineteenth century, the peyotl cult spread among Native American peoples in the Southwest United States. The spread of peyotl knowledge is recognized among Indigenous peoples in Oklahoma, mainly the Comanche and the Kiowa, but also in Arizona among the Diné or Navajo. Peyotl knowledge is found in the prairies of Canada, notably in Saskatchewan, far from the Southwestern United States.

6. Implications

By the end of the nineteenth century, the Native American Church of Jesus Christ (NAC) arose in the context of the United States government’s 1890 ban of Ghost Dance rituals in the U.S. After the ban, NAC members considered the sacramental use of peyotl (peyote) to be at the core of their ritual practices. The peyotl cult grew rapidly among Native American peoples in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The NAC is considered a counterbalance against colonialism.

First practiced in 1889, responding to massive land seizures and cultural assimilation, Ghost Dance rituals were large-scale ceremonies involving hundreds of participants in a circle dance. These rituals were declared to reconnect with the Ancestors, to acknowledge a Native American way of life, and to symbolically end colonial expansion. Ghost Dance rituals frightened settlers and authorities, and the U.S. government banned them.

The Native American Church emerged to protect the religious freedom of its members. Peyotl is considered a medicine and a divine gift that provides counseling and strength to deal with colonial legacies of discrimination, lack of recognition, and the lack of medical services. NAC rituals sacramentally use peyotl for its therapeutic properties, treating mental and spiritual health issues. [14] NAC rituals are usually performed during the night inside a tipi and around a bushfire where chants and sacred narratives are displayed by a ritual specialist known as a roadman or medicine man.

The Native American Church of Jesus Christ gained official recognition in 1918, but, since its beginning, NAC members were harassed, prosecuted, and incarcerated by the U.S. Government. The United States government has attempted to make the NAC illegal, and many states introduced anti‐peyote legislation throughout the first half of the twentieth century. Due to the NAC’s organization as a legal and recognized church, the result of protracted legal disputes, the NAC survives and thrives, increasing the number of church affiliates and winning court cases.

The peyotl cult in the NAC has been considered a counterbalance against colonialism and emerged from mass resistance by Native Americans. The NAC continues efforts to raise ecological awareness regarding the peyote preservation [15], for peyotl is now a plant species under threat due to unsustainable consumption as well as narrow range of peyotl-bearing lands being developed, agricultural competition, and border enforcement.

References

[1] Schaefer, Stacy B. “The Crossing of the Souls: Peyote, Perception and Meaning among the Huichol Indians.” In People of the Peyote: Huichol Indian History, Religion, & Survival, edited by Stacy B. Schaefer and Peter T. Furst (University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 141.

[2] Schultes, Richard Evans, Albert Hofmann, and Christian Rätsch. Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing and Hallucinogenic Powers (Healing Arts Press, 1992), 63.

[3] Schaefer, Stacy B. “The Crossing of the Souls: Peyote, Perception and Meaning among the Huichol Indians.” In People of the Peyote: Huichol Indian History, Religion, & Survival, edited by Stacy B. Schaefer and Peter T. Furst (University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 142.

[4] Narváez Elizondo, Raúl, Luis Encarnación Silva Martínez, and William Breen Murray. “El brebaje del desierto: usos del peyote (Lophophora williamsii, Cactaceae) entre los cazadores-recolectores de Nuevo León.” Desde el herbario CICY 10, (2018): 189.

[5] Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH). “Hallan vestigios de los primeros pobladores del territorio que hoy ocupa Nuevo León.” Boletín 291, May 13, 2023. https://www.inah.gob.mx/boletines/hallan-vestigios-de-los-primeros-pobladores-del-territorio-que-hoy-ocupa-nuevo-leon.

[6] Boyd, Carolyn Elizabeth. “The Work of Art: Rock Art and Adaptation in the Lower Pecos, Texas Archaic.” (PhD diss., Texas A&M University, 1998), 126.

[7] Samorini, Giorgio. “The Oldest Archeological Data Evidencing the Relationship of Homo Sapiens with Psychoactive Plants: A Worldwide Overview.” Journal of Psychedelic Studies 3, no. 2 (2019): 71.

[8] Jay, Mike. Mescaline: A Global History of the First Psychedelic. (Yale University Press, 2019), 34.

[9] Rafferty, Sean M. “Prehistoric Intoxicants of North America.” In Ancient Psychoactive Substances, edited by Scott Fitzpatrick (University Press of Florida, 2018), 120.

[10] Bruhn, J. G., J. E. Lindgren, B. Holmstedt, and J. M. Adovasio. “Peyote Alkaloids: Identification in a Prehistoric Specimen of Lophophora from Coahuila, Mexico.” Science 199, no. 4336 (1978): 1437-1438.

[11] Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH). “Hallan vestigios de los primeros pobladores del territorio que hoy ocupa Nuevo León.” Boletín 291, May 13, 2023. https://www.inah.gob.mx/boletines/hallan-vestigios-de-los-primeros-pobladores-del-territorio-que-hoy-ocupa-nuevo-leon.

[12] Sahagún, Bernardino de. Florentine Codex (General History of the Things of New Spain). Book X. Chapter XXIX. Translated by Charles E. Dibble and Arthur Anderson. (The School of American Research and the University of Utah, 1961), 173.

[13] Schultes, Richard Evans. “Iconography of New World Plant Hallucinogens.” Arnoldia 41, no. 3 (1981): 94.

[14] Calabrese, Joseph D. A Different Medicine: Postcolonial Healing in the Native American Church. (Oxford University Press, 2013), 17-18.

[15] González Romero, Osiris. “Decolonizing Peyote Politics in Mexico and Southwest U.S.” In Struggles for Liberation in Abya Yala, edited by Ernesto Rosen and Luis Ruben Díaz (Wiley, 2024), 285-286.

Peyotl or Hikuri, Peyote, Lophophora williamsii

Kauyumarie’s Nierika

Indigenous Cultures of Northern Mexico and Southwestern U.S.

Image 1. Kauyumarie’s Nierika. José Benítez Sánchez. Yarn Painting, 1974. Mixed media: plywood, beeswax, and wool yarn. Photograph by Juan Negrín. Wixárika Research Center.

Image 2. Lophophora williamsii (Lem. ex Salm-Dyck) J.M.Coult. Observed in Mexico by altamiranohg and presented at iNaturalist. https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/245787140

Image 3. Map of Peyote Distribution. Reproduced from Boyd, Carolyn Elizabeth. [6]

Image 4. Illustration of Lophophora Williamsii (Lem.) by Coulter, listed as Echniocactus Williamsii Lemaire in Bot. Mag. 73 (1847) t. 4296. [13]