Morning Glory; Coaxihuitl, “Snake Plant,” and Ololiuhqui, “Round Thing”; Semillas de la Virgen, “Seeds of the Virgin”; Ipomoea corymbosa

Teotihuacán Murals, Abuela Medicina (Medicine Grandmother) by Asunción Alvarado

Teotihuacan, Nahua and Mazatec Cultures

1. Name

Because of the wide range of Indigenous, Spanish, and botanical names for the plant and seeds of the Ipomoea corymbosa, this entry will favor the English name, “morning glory.” The morning glory plant has recently been botanically reclassified as Ipomoea corymbosa, but earlier scientific and anthropological research used the prior term, “Turbina corymbosa.”

The morning glory has a range of names throughout Mesoamerica. In Spanish, it is called “semillas de la Virgen,” meaning seeds of the Virgin (Mary). In Nahuatl, it is called ololiuhqui, which means “round thing.” In the Chinantec language from Oaxaca, México, it is known as “A-mu-kia,” which means “medicine for divination.” [1] In Indigenous languages, here and generally, botanical names require further study by linguists to explore their meanings and associations.[2]

Some cultures, such as among the Nahua, distinguish between the plant/vine and the seeds it produces. The Ipomoea corymbosa vine is known in the Nahuatl language by the name “coaxihuitl,” which means “snake plant.” It is also often known in the Nahuatl language by the name “ololiuhqui,” the name of its seeds, meaning “round thing.” The seeds are small brown ovals. The Ipomoea corymbosa plant itself, the vine that produces ololiuhqui, is a climbing vine. When they climb trees, the vines resemble snakes climbing a tree trunk. The vine is also named “hiedra” or “bejuco” by Spanish writers. [3]

2. Introduction and Artwork

The morning glory vine may be considered and depicted as a deity, or the images may depict the plant as a healer and a healing ritual. There appears to be a Mesoamerican “hard nucleus” in which cultural features are shared by different civilizations across eras and regions: water deities are related to fertility and the vegetal world across cultures. As shown below, the morning glory is associated with fertility and gynecology. Furthermore, the morning glory plant is connected to Psilocybe mushrooms, healing rituals, and healers.

Anthropologist Peter Furst proposes that the front-facing female deity featured in Image 1 is a metaphysical conception of the morning glory vine. This image is found at the center of the Tlalocan mural, the Paradise of Tlaloc, at the pre-Colombian site Tepantitla, in the sacred city of Teotihuacan, northeast of Mexico City.

Responding to challenges of his interpretation, Furst explains that “We are generally agreed that the frontal deity is indeed female and that she seems to represent the Earth Mother in a youthful and bountiful aspect. [Esther] Pasztory believes that she comes closest in character to Xochiquetzal (Precious, or Quetzal, Flower), the young Earth Mother and creator goddess of fertility and vegetation […]. As fountainhead of terrestrial water, which pours from the area of her nose and mouth, she seemed to me to embody primarily the characteristics of Chalchiuhtlicue, Lady of the Jade Skirt, goddess of water that flows over and under the earth, mother of springs, streams, lakes and water holes, and, according to some traditions, wife, or sister, of Tlaloc.” [4]

Furst’s iconographic identification requires support by more archeological evidence, for his interpretation could be a backward projection of Aztec cultural features onto the Teotihuacan civilization (100 CE-700 CE) that predates the Aztecs (1300-1521).

Asunción Alvarado, a Mazatec contemporary artist from the Sierra Mazateca region of Oaxaca, depicts a range of sacred plants and fungi, including the morning glory, in his work. In Image 2, the painting Abuela Medicina (Medicine Grandmother) portrays the Ipomoea corymbosa vine growing from the bottom of the painting, extending its branches to both sides, climbing to the top. The background of the painting is a starry sky. The imagery of the vine is accompanied by imagery of Psilocybe mushrooms—those mushrooms containing the psychedelic compounds psilocin and psilocybin—and Salvia divinorum, suggesting a sacred status of these plants and fungi.

At the painting’s center, a ritual incense burner with a luminous yellow fire sheds light. The leaves of the morning glory plant are clearly depicted, and their stems appear to undulate like a moving snake. The purple flowers, found in the middle and toward the top, identify the plant as the morning glory. Luminous purple hummingbirds radiate an orange aura as they fly, looking toward the edge of the frame. At both sides of the burner are depicted leaves from the ská pastora (Salvia divinorum), another sacred and psychedelic plant. Surrounding the fire are the blue shapes of six sacred Psilocybe mushrooms.

At the top and center is depicted a realistic female face of a wise woman or ritual specialist (chotaj chinej): Mazatec doctors who ritually deploy morning glory or Psilocybe mushrooms to treat patients. Asunción Alvarado explains that the “seeds of the Virgin, or ololiuhqui, were used in ancient times for divination and healing, just like other mystical and sacred plants of the Mazatec people. Today, very few wise men and women still use them. The seeds are held in high regard, as they must be handled with great care by a wise person who knows the seeds well.” [5] Alternatively, the depiction in Image 2 can be interpreted to parallel the plant as a deity in the ancient Tepantitla Murals.

3. Geography and Context

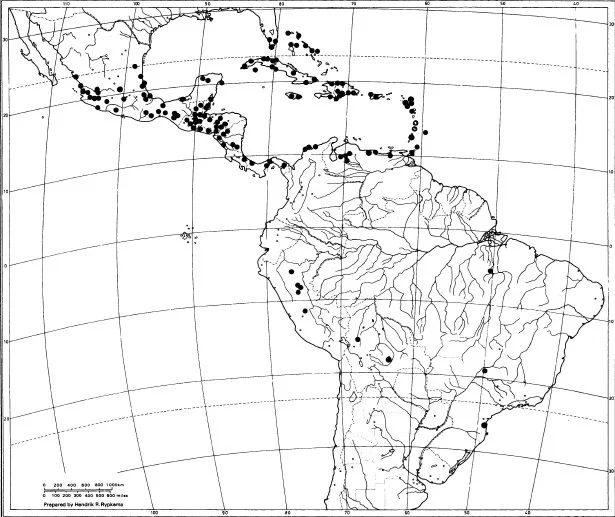

The Ipomoea corymbosa, or “morning glory,” is widely distributed throughout the Americas, especially in warm areas. (Image 3) The morning glory was previously classed as Turbina corymbosa, but it is now considered an Ipomoea. This distinction is not noted in earlier scholarship; therefore, Turbina corymbosa should be understood to be Ipomoea corymbosa. “Turbina corymbosa has a vast range on the American continental mainland, from Mexico southward throughout Central America into South America as far as Bolivia and southern Brazil. It is also found throughout the West Indies, the Bahamas, and Bermuda.” [7]

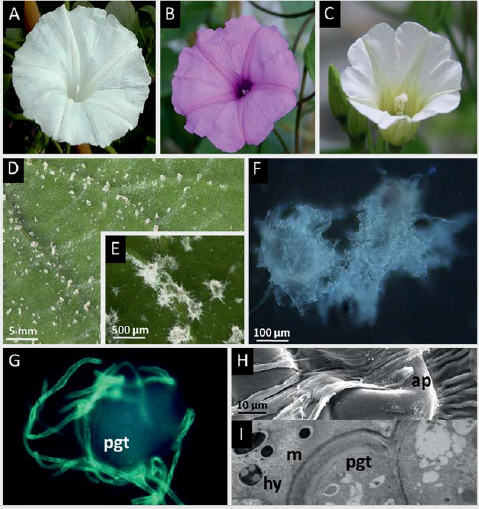

In Mesoamerica, the morning glory natively grows in Central and Southeast Mexico. In Oaxaca, another species called “badoh negro” in Spanish, with the botanical name “Ipomoea violacea,” has long been used ritually and therapeutically by Native American peoples. Both Ipomoea corymbosa and Ipomoea violacea have psychedelic principles. “Violacea” means “purple,” referring to its flower, and is more potent than the Ipomoea corymbosa. “Corymbosa” means “a cluster,” referring to its flowers. (Image 4)

Simple chemical compounds in the morning glory, such as lysergic amides, belong to the psychedelic chemical family of ergot alkaloids known as ergines. Lysergic amides are structurally close to lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Albert Hofmann, the chemist who discovered LSD, isolated the active principle chemicals in morning glory seeds, identifying the psychedelic alkaloids ergine and isoergine as well as the non-psychedelic alkaloids canoclavine, elimoclavine, and lysergol.[8] Cutting-edge research posits that the psychedelic properties in the morning glory developed from these vines’ evolutionary symbiosis with an ergot-spreading fungi species called Periglandula ipomoea. That symbiosis transferred the fungi’s psychedelic chemical principles into the seeds of the plant.[9]

4. Primary Sources and Evidence

Historical evidence for the cultural use of Ipomoea corymbosa and Ipomoea violacea, morning glory vines with different flowers, can be located in early manuscripts and chronicles composed by Spanish missionaries in Mexico, including the sixteenth-century ethnographic Florentine Codex and Francisco Hernández’s seventeenth-century medical text titled Rerum Medicarum Novae Hispaniae Thesaurus, "Treasury of Medical Matters of New Spain."

Book XI, Chapter VII of the Florentine Codex explains the therapeutic and visionary properties of the morning glory as found in Nahua culture. “It leaves are slender, cord-like, small. Its name is ololiuhqui. It makes one besotted; it deranges one, troubles one, maddens one, makes one possessed. He who eats, who drinks it, sees many things which greatly terrify him. He is really frightened [by the] poisonous serpent, which he sees for that reason […] He who hates people causes one to swallow it in drink and food to madden him. However it smells sour; it burns the throat a little. For gout it is only spread on the surface.” [11] The clash of different cultural paradigms when the Spanish encountered the Nahuas fosters this dismissive colonial perspective.

Francisco Hernández writes about the morning glory as Turbina corymbosa. Hernández was a Spanish physician sent by King Philip II on a seven-year research expedition (1570-77) to survey the therapeutic properties of New World plants, cacti, and fungi. “The T. corymbosa plant heals the syphilis, after exposure to cold or distortion and fracture of a bone the plant–when mixed with some resin–alleviates the pain by increasing body strength, drives out flatulence and controls an unnatural surge. Crushed seeds help to cure diseases of the eyes when extracts mixed with milk and chili are applied to head and forehead, stimulate sexual interaction after ingestion, crushed seeds smell strong and are mildly warm. During divination when Indians contact their gods and ask for answers they ingest plant material, go mad, develop visions and view daemons. When suffering from gout pulverized seeds suspended in oil from Abies spec. or in white honey.” [12] The range of Indigenous uses for morning glory spans from clinical treatments, including sexual and optic diseases and gout, to divination and visionary uses.

5. Interpretation

Ipomoea corymbosa and Ipomoea violacea, both vines called “morning glory” in English, and their seeds, have been used by Mesoamerican peoples for centuries, perhaps millennia. Indigenous iconographic evidence and varied historical sources document therapeutic, sacramental, and divinatory uses of morning glory throughout Mesoamerica. While Colonial physicians sought to understand medical properties, the plants and their psychedelic use were condemned, and users were persecuted. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Colonial sources document the morning glory plants’ cultural significance and wide distribution throughout Mesoamerica.

Because these plants could alleviate syphilis symptoms and treat gynecological issues, both plants in the Aztec worldview were symbolically related to fertility deities such as Xochipilli and Xochiquetzal. Supernatural forces were thought to inhabit the plant because their psychedelic properties allowed communication with deities, some belonging to Mesoamerican traditions and others that are Catholic and syncretic.

A distinctive feature that makes these plants unique is that their psychedelic properties, namely their ergot alkaloids, originate from atypical evolutionary symbiosis with the fungi Periglandula ipomoea. [13] Strictly speaking, this fungus is the source of the ergot alkaloids that contain the psychedelic principle compounds found in morning glory plant seeds. It seems that the symbiosis is only present in these plants and not others found in conjunction with Periglandula ipomoea.

6. Implications

Connections of morning glory to gynecology, fertility, and venereal disease treatments are backed by Indigenous knowledge and contemporary scientific research, suggesting that the morning glory will play a prominent part in future ethnogynecology. Despite the psychological emphasis on sacred plants in current psychedelic research, the therapeutic potential of psychedelic plants is not exclusively related to mental health conditions, as demonstrated by morning glory treating a broad range of illnesses unrelated to the mind or the soul.

The morning glory’s therapeutic potentials continue to be discovered. Regarding therapeutic potentials, recent research shows that: “The peptide ergot alkaloid exhibits a strong uterotonic activity. It is a vasoconstrictor, which is mainly used against migraine. Ergotamine is the only naturally occurring ergot alkaloid that is still in use as medication in Germany . . . Ergots alkaloids were developed into semisynthetic compounnds carryng the ergoline core. . .They are used in obstetrics, against female infertility, Parkinson’s disease, or for the cognitive improvement of the elderly.” [14]

Acknowledging Indigenous knowledge of the morning glory and this sacred plant’s uses reveals not only wide-ranging future therapeutic uses but also can remedy ongoing problems surrounding the unethical extraction of plants revered by Native cultures. Indigenous people always considered morning glory plants, whether Ipomoea corymbosa and Ipomoea violacea, to be means to communicate with deities and not merely therapeutic substances, i.e., drugs. Greater knowledge of the cultures around these plants fosters greater responsibility and fewer hasty generalizations regarding these plants and the cultures that revere them.

References

[1] Schultes, Richard Evans, Albert Hofmann, and Christian Rätsch. Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing and Hallucinogenic Powers. (Healing Arts Press, 1992), 173.

[2] Wasson, Robert Gordon. “Notes on the Present Status of Ololiuhqui and the Other Hallucinogens of Mexico.” Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University 20, no. 6 (1963): 175.

[3] Wasson, Robert Gordon. “Notes on the Present Status of Ololiuhqui and the Other Hallucinogens of Mexico.” Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University 20, no. 6 (1963): 175.

[4] Furst, Peter. “Morning Glory and Mother Goddess at Tepantitla, Teotihuacán: Iconography and Analogy in Pre-Columbian Art.” In Mesoamerican Archaeology: New Approaches, edited by Norman Hammond (University of Texas Press, 1974), 198.

[5] Alvarado, Asunción. Personal communication, June 26, 2025.

[6] Austin, Daniel F., and George W. Staples. “A Revision of the Neotropical Species of Turbina Raf. (Convolvulaceae).” Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 118, no. 3 (1991): 275.

[7] Austin, Daniel F., and George W. Staples. “A Revision of the Neotropical Species of Turbina Raf. (Convolvulaceae).” Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 118, no. 3 (1991): 274.

[8] Hofmann, Albert. “The Active Principles of the Seeds of Rivea Corymbosa and Ipomoea Violacea.” Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University 20, no. 6 (1963): 206.

[9] Steiner, Ulrike, and Eckhard Leistner. “Ergot Alkaloids and Their Hallucinogenic Potential in Morning Glories.” Planta Medica 84, no. 11 (2018): 755.

[10] Steiner, Ulrike, and Eckhard Leistner. “Ergot Alkaloids and Their Hallucinogenic Potential in Morning Glories.” Planta Medica 84, no. 11 (2018): 754.

[11] Sahagún, Bernardino de. Florentine Codex (General History of the Things of New Spain). Book XI. Translated by Charles E. Dibble and Arthur Anderson. (The School of American Research and the University of Utah, [1963] 1975), 129.

[12] Steiner, Ulrike, and Eckhard Leistner. “Ergot Alkaloids and Their Hallucinogenic Potential in Morning Glories.” Planta Medica 84, no. 11 (2018): 752-753; Schultes, Richard Evans, Albert Hofmann, and Christian Rätsch. Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing and Hallucinogenic Powers. (Healing Arts Press, 1992), 170.

[13] Steiner, Ulrike, and Eckhard Leistner. “Ergot Alkaloids and Their Hallucinogenic Potential in Morning Glories.” Planta Medica 84, no. 11 (2018): 755-756.

[14] Steiner, Ulrike, and Eckhard Leistner. “Ergot Alkaloids and Their Hallucinogenic Potential in Morning Glories.” Planta Medica 84, no. 11 (2018): 756.

Image 1. A possible female deity. Tepantitla Murals, Teotihuacan, México 200 CE. Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City.

Image 2. Abuela Medicina (Medicine Grandmother) by Asunción Alvarado, 2023.

Image 3. Locations where Ipomoea corymbosa grows. The morning glory plant grows easily and abundantly in the mountains of Southern Mexico, as well as in the Caribbean and South America. [6]

Image 4. Flowers of Ipomoea plants juxtaposed with the mycelium of the ergot spreading Periglandula fungi.[10]