Image 1. Tlalocan or “Paradise of Tlaloc” mural, Tepantitla Murals. Teotihuacan, México 200 AD.

2. Introduction and Artwork

Anthropologist Peter Furst proposes thatd the front-facing female deity featured at the center of the Tlalocan or “Paradise of Tlaloc” mural (Image 1) at the pre-Colombian site TepantitIa, in the sacred city of Teotihuacan, is a metaphysical conception of the morning glory vine. He explains, responding to challenges, that We are generally agreed that the frontal deity is indeed female and that she seems to represent the Earth Mother in a youthful and bountiful aspect. Pasztory believes that she comes closest in character to Xochiquetzal (Precious, or Quetzal, Flower), the young Earth Mother and creator goddess of fertility and vegetation […]. As fountainhead of terrestrial water, which pours from the area of her nose and mouth, she seemed to me to embody primarily the characteristics of Chalchiuhtlicue, Lady of the Jade Skirt, goddess of water that flows over and under the earth, mother of springs, streams, lakes and water holes, and, according to some traditions, wife, or sister, of Tlaloc.” (Furst, 1974:198).

Furst’s iconographic identification requires support by more archeological evidence, for the interpretation may be a backward projection of Aztec cultural features rather than being from the Teotihuacan civilization (100 CCE-700 CE) itself, which predates the Aztecs (1300-1521). There appears to be a Mesoamerican “hard-nucleus” in which , cultural features are shared by different civilizations across eras and regions:. Water deities are related to fertility and the vegetal world across cultures.

Mazatec contemporary artists, such as Asunción Alvarado, from what is now the Sierra Mazateca region of Oaxaca, depict a wide array of sacred plants and fungi in their work, including the morning glory. In Image 2, Alvarado portrays the vine of Ipomoea corymbosa, growing from the bottom of the painting, extending its branches to both sides, climbing to the top. The background of the painting is a starry sky.

The leaves of the plant are clearly depicted, and the stem appears to undulate like a moving snake. The purple flowers, found at the middle and toward the top, serve to identify the plant as the morning glory., Luminous purple humming birds radiate an orange aura as they fly, looking towards the edge of the frame.

At the center, a ritual incense burner with a luminous yellow fire sheds light., At both sides of the burner are depicted leaves from the ská pastora (Salvia divinorum), another sacred plant. Surrounding the fire are , the blue shapes of six sacred mushrooms, likely psilocybe mushrooms, containing the psychedelic compounds psilocin and/or psilocybin. At the top and center is depicted a realistic a female face ,resembling a wise woman or rituals specialist (chotaj chinej).

Regarding the artwork symbolism, the artist, Asunción Alvarado, explains that the “seeds of the Virgin”, or ololiuhqui, were used in ancient times for divination and healing, just like other mystical and sacred plants of the Mazatec people. Today, very few wise men and women still use them. The seeds are held in high regard, as they must be handled with great care by a wise person who knows the seeds well”.(Personal Communication ,June 26, 2025).

3. Geography and Context

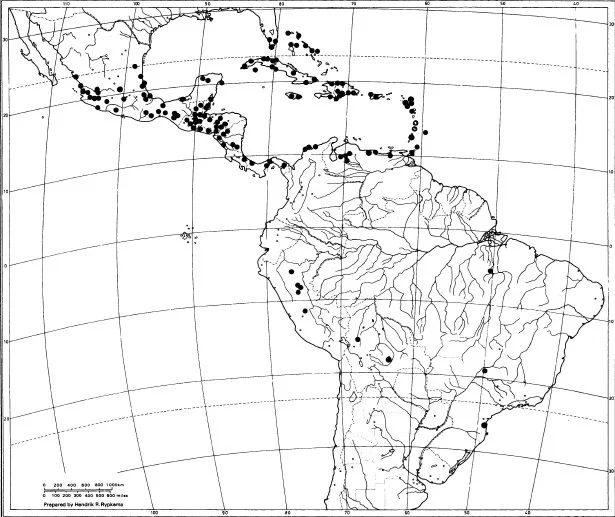

Ipomoea corymbose, morning glory in English, is widely distributed in the Americas, especially in warm areas, and its flowering coincides with the last rains of the Central American Monsoon season, spanning May to November. “Turbina corymbosa has a vast range on the American continental mainland, from Mexico southward throughout Central America into South America as far as Bolivia and southern Brazil. It is also found throughout the West Indies, the Bahamas, and Bermuda” (Austin and Staples 1991, 274-275). The morning glory was previously classed asTurbina corymbose, but it is now considered an Ipomoea.

In Mesoamerica, the morning glory grows in Central and Southeast Mexico. In Oaxaca, another species called badoh negro, with the botanical name Ipomoea violacea, has long been used by Indigenous peoples for ritual and therapeutic purposes. Both Ipomoea corymbosa and Ipomoea violacea have psychedelic principles. Ipomoea violacea—“violacea” means purple, regarding its flower—is more potent than the Ipomoea corymbosa—“corymbosa” meaning a cluster, referring to its flowers.

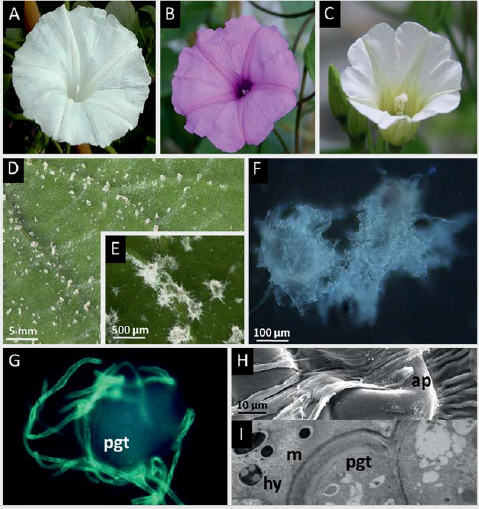

Simple chemical compounds in the morning glory, such as lysergic amides, belong to the psychedelic chemical family of ergot alkaloids. Lysergic amides are structurally close to LSD, lysergic acid diethylamide. As he reported in1963, from morning glory seeds, Albert Hofmann, the chemist who created LSD, isolated the active principle chemicals ergine, isoergine, canoclavine, elimoclavine, and lysergol. The psychedelic properties in morning glory, in fact, developed from these vines’ evolutionary symbiosis with a fungi species called Periglandula, transferring the fungi’s’ chemical principles to the seeds of the plant. (Steiner and Leistner 2018, 754).

4. Primary Sources and Evidence

Historical evidence for the cultural uses of Ipomoea corymbosa and Ipomoea violacea, i.e., morning glory, can be located in early manuscripts and the chronicles of Spanish missionaries in Mexico, such as presented below in the sixteenth-century ethnographic Florentine Codex and in Francisco Hernández’s seventeenth-century medical text Rerum Medicarum Novae Hispaniae Thesaurus.

Book XI Chapter VII of the Florentine Codex, explains therapeutic and visionary properties of morning glory in Nahuatl cultures.: “It leaves are slender, cord-like, small. Its name is ololiuhqui. It makes one besotted; it deranges one, troubles one, maddens one, makes one possessed. He who eats, who drinks it, sees many things which greatly terrify him. He is really frightened [by the] poisonous serpent, which he sees for that reason […] He who hates people causes one to swallow it in drink and food to madden him. However it smells sour; it burns the throat a little. For gout it is only spread on the surface.” (Sahagún 1973, 129). A dismissive colonial gaze is clearly present, due to the clash of different cultural paradigms when the Spanish encountered the Nahuatl..

Francisco Hernández was, a Spanish physician sent by the King Philip II on a seven year research expedition (1570-77) to survey of the therapeutic properties of New World plants, cacti, and fungi. Iin the book, “Rerum Medicarum Novae Hispaniae Thesaurus (1648/49)s, ” Hernandez writes about the morning glory as Turbina corymbosa, translated below from Latin.: “The T. corymbosa plant heals the syphilis, after exposure to cold or distortion and fracture of a bone the plant–when mixed with some resin–alleviates the pain by increasing body strength, drives out flatulence and controls an unnatural surge. Crushed seeds help to cure diseases of the eyes when extracts mixed with milk and Chili are applied to head and forehead, stimulate sexual interaction after ingestion, crushed seeds smell strong and are mildly warm. During divination when Indians contact their gods and ask for answers they ingest plant material, go mad, develop visions and view daemons. When suffering from gout pulverized seeds suspended in oil from Abies spec. or in white honey. (Steiner and Leistner 2018, 751; Schultes, Hofman and Rätsch 1992, 170-171). Therefore, the range of Indigenous uses for morning glory spanned from clinical treatments, including sexual and optic diseases and gout, to divination and visionary uses.

5. Interpretation

Ipomoea corymbosa and Ipomoea violacea, two vines both called morning glory in English, and their seeds have been used by Indigenous Mesoamerican peoples for centuries, perhaps millennia. During colonial times, the plants and their psychedelic as well as therapeutic uses were condemned, and users were persecuted. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Colonial sources document morning glory plants’ cultural significance and wide distribution throughout Mesoamerica. Indigenous iconographic evidence and varied historical sources document (therapeutic, sacramental, and divinatory cultural uses) of morning glory throughout Mesoamerica..

Within the Aztec worldview, both plants were symbolically related with fertility deities, such as , (Xochipilli and Xochiquetzal,) because it could alleviate syphilis symptoms and treat gynecological issues. Both plants were widely considered sacred because supernatural forces inhabited the plant and also, because their psychedelic properties allowed communication with deities, some who were traditionally Mesoamerican tradition and others Catholic and syncretic.

A distinctive feature, which makes these plants unique, is that their psychedelic properties, namely their , ergot alkaloids, originate from atypical evolutionary symbiosis with the fungi Periglandula ipomoea (Steiner and Leistner 2018, 754). Strictly speaking, this fungi is the source of the ergot alkaloids that, contains the psychedelic principle compounds found in morning glory plant seeds.

6. Implications

Acknowledging Indigenous knowledge of this sacred plant and its uses is especially important to understand not just the plant and its possible future therapeutic uses, aiming to avoid the ongoing ethical problems of extraction, but for understanding the cultures that revere these plants. Records highlight morning glory’s therapeutic properties, especially for venereal diseases, reproductive health, and gynecology. These plants therapeutic potentials continue to be discovered..

Morning glory plants, whether Ipomoea corymbosa and Ipomoea violacea, were deemed as sacred in themselves, though they were also considered symbolically rich and were believed to be an ancestor. Morning glory plants’and their use were always considered means to communicate with deities. .

Regarding their therapeutic potentials, recent research shows that, the “peptide ergot alkaloid exhibits a strong uterotonic activity. It is a vasoconstrictor, which is mainly used against migraine. Ergotamine is the only naturally occurring ergot alkaloid that is still in use as medication in Germany […]Ergots alkaloids have been used in obstetrics, against female infertility, Parkinson´s decease, or for the cognitive improvement of the elderly. ”(Steiner and Leistner 2018, 755)

The symbolic connections of this plant with gyinecology, fertility,and venereal decease treatments are backed by indigenous knowledge and contemporary scientific research. Despite the clinical psychological emphasis in current research, the therapeutic potential for psychedelic plants are not exclusively related with mental health conditions. Psychedelic plants, can treat a broader range of illnesses unrelated to the mind or the soul..

References:

Austin, Daniel F., and George W. Staples. “A Revision of the Neotropical Species of Turbina Raf. (Convolvulaceae).” Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 118, no. 3 (1991): 265–80. https://doi.org/10.2307/2996641.

Furst, Peter. “Morning Glory and Mother Goddess at Tepantitla, Teotihuacán: iconography and analogy in pre-Columbian art”. In Hammond, N (ed). Mesoamerican Archaeology: New Approaches. (University of Texas Press, 1974), 187-215.

Hofmann, Albert. “The active principles of the seeds of Rivea Corymbosa and Ipomoea Violacea.” Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University 20 (6), (1963):194–212. https://doi.org/10.5962/p.168542.

Sahagún, Bernardino de. Florentine Codex (General History of the Things of New Spain). Book XI. Trans by Charles E. Dibble and Arthur Anderson. (The School of American Research and the University of Utah 1975), 129.

Schultes, R.E, Hofmann, Albert and Rätsch, Carl. Plants of the Gods Their Sacred, Healing and Hallucinogenic Powers. (Healing Arts Press, 1992):170-175.

Steiner, Ulrike, and Eckhard Leistner. 2018. “Ergot Alkaloids and Their Hallucinogenic Potential in Morning Glories.” Planta Medica 84 (11): 751–58. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0577-8049

Wasson, Robert. Gordon. “Notes on the Present Status of Ololiuhqui and the Other Hallucinogens of Mexico.” Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University 20 (6) (1963): 161–93. https://doi.org/10.5962/p.168541.

Image 2. By Asunción Alvarado, ©. Mazatec Visionary Artist

Image 3. Map of Central and South America (Austin and Staples 1991, 269)

Image 4. Flowers of Ipomoea and mycelium of Periglandula fungi (Steiner and Leistner 2018, 754)

Image 5. LA ABUELA PASTORA by RENÉ ALVARADO

Coaxihuitl, Ololiuhqui, Snake Plant, Seeds of the Virgin (Morning Glory)

Nahua & Mazatec Cultures

1. Name

The Ipomoea corymbosa vine, commonly known in English as morning glory, is known in Nahuatl language by the names coaxihuitl that means “snake plant,” and, also means“turquoise serpent.” It often is known in Nahuatl language by the name of its seeds, ololiuhqui meaning “round thing.”

The morning glory has a range of names throughout Mesoamerica. In Spanish, it is“semillas de la Virgen.” meaning seeds of the Virgin (Mary). In Zapotec, a southern Mesoamerican language, he morning glory is known as badoh, and its. Seeds are called badoh negro. In the Chinantec language, it is known as: A-mu-kia: “medicine for divination.”” (Schultes, Hofmann and Rätsch 1992, 173). Indigenous languages names require further study by linguists to explore their meanings and associations.”. (Wasson 1963, 175).In the Nahuatl language, ololiuhqui is the name of the morning glory’s seeds and, not the name of the plant that yields the seeds. In a broad sense, the word ololiuhqui means “round thing.”The seeds are small, brown ovals. The plant itself is a climbing vine, called coaxihuitl, meaning “snake-plant” in Nahuatl language, for snakes climbing trees resemble a climbing vine on a tree trunk. It is also named hiedra or bejuco by Spanish writers. (Wasson 1963, 175).The morning glory plant has recently has been reclassified asIpomoea corymbosa, but earlier scientific and anthropological research considered itTurbina corymbosa. The morning glory grows easily and abundantly in the mountains of Southern Mexico.