Peyotl or Hikuri, Peyote

Kauyumari's Nierika

Indigenous Cultures of Northern Mexico and Southwest U.S.

1. Name

Known in English as peyote, the names of these sacred cacti—peyotl, hikuri, jikuli or /jiculí—come from languages belonging to the Uto-aztecan langugeinguistic family, spoken throughout western Mesoamerica and the Western United States. Anthropologist and peyote scholar Stacy B. Schaefer explains that, “Since peyote first come under scrutiny of western botanists and psychopharmacologists it has gone through a series of name changes, until science settled in Lophophora for the genus and williamsii and diffusa for the two species of peyote that have been positively identified.” (Schaefer 1996, 141)

The Nahuatl name peyotl can be translated “silk cocoon.” Hikuri translated “mirror” and “moon,”— is another name for peyote in Huichol, the Wixárika language Huichol. Jikuli or Jiculíare names for peyote used by Raramuris or (Tarahumaras), Coras, and Tepehuanes, all: peoples,, along with the others mentioned above, who who maintain sacramental use of these cacti. Art historians have also registered the sacramental use by Lipán Apaches in the plains of Northern Mexico and Texas, and by Teochichimecas, a wide-ranging nomadic people in Central Mexico. This entry will favor the Nahuatl name peyotl.

2. Introduction and Artwork

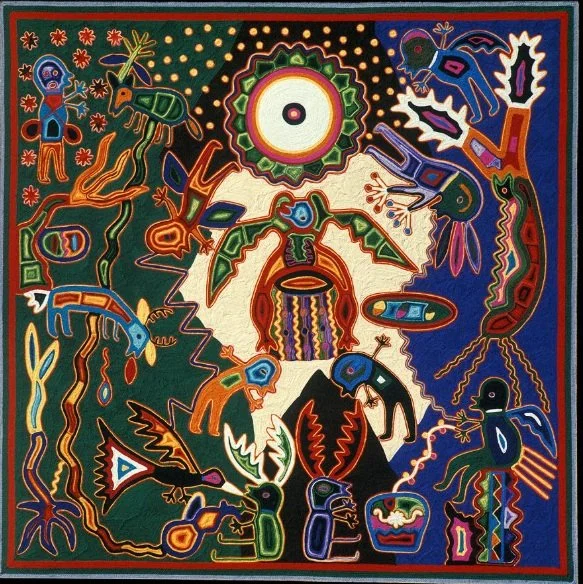

José Benítez Sánchez’s yarn painting titled “Kauyumarie's Nierika” (Image 1) illustrates the Wixárika cosmogony tale in which the gods emerge from the underworld and come to the Earth. The Blue Deer named Kauyaumarie, meaning Our Old Brother Deer, found the nierika, a luminous circle, that is a gateway to the spirit world. His nierika, the radiant disk at the top of the image, a common element in Wixárika art and mythology, unifies the spirit of physical beings and the spirit worlds. Beings come to life through the nierika. The lines stretching out from the center on physical peyotl (peyote) buttons are thought to resemble the cosmological paths of the sacred Blue Deer in this tale. Below the nierika, Our Mother Eagle opens her wings, and she bows her head to listen to Kauyumarie, who sits on a rock, below and to the right, on a rock. Kauyumarie’s words descend on a thread and into a vessel, transforming his speech into vital energy that is depicted as a white flower. Above Kauyumarie, the spirit of Rain, in the form of a serpent with deer horns, gives life to the gods who stretch around these images as they spread across the earth. (Schultes, Hofmann and Rätsch 1992).3. Geographical distribution

Peyotl (peyote) grows mainly in Northern Mexicano and Southern Texans in desert regions in special ecological zones with the right soil for the cacti to thrive.Lophophora williamsi is native into the high desert region of San Luis Potosí, which the Huichols called Wirikuta, as well in parts of the Mexican states of Zacatecas and Coahuila, and in the South Texas plains along the Lower Río Grande. Lophophora diffussa, a cactus of the same family that is only mildly psychoactive, on the other hand, is only observed growing in a small desert zone in the Mexican State of Queretaro. (Schaefer 1996, 141-142).

Recent archeological research discovered seeds and peyote bottoms, along with petroglyphs, in the Mexican state of Nuevo León an understudied region. (Narvaez, et al, 2018) Archeologists found peyote seeds in Villaldama, an ancient archeological site in Northeeastern Mexico that dates from 14,000 BCE. There are no data regarding radiocarbon tests on the seeds and buttons, but other artifacts there, such flint arrows, have been dated to 6000 BCE.

4. Primary Sources and Evidence

Archaeological evidence locates peyotl (peyote) buttons in prehistoric sites found throughout what is now Texas and Northern Mexico. Analysis of rock art, ceramic vessels, iconography, colonial sources, codices, chronicles reveals a long history of peyotl use in the Americas. Discuss-shaped, dried peyotl buttons were discovered near ancient rock art in the Shumla caves on the Texas side of the Rio Grande river (Samorini 2019). These preserved buttons are have been radiocarbon dated to approximately four thousand years BCE, and they shown to still contain mescaline at a concentration around two percent (Jay 2019).Several cave and rock-shelter sites in Texas contain preserved peyotl whose radiocarbon dates range between 5000 and 5700 BCE” (Rafferty 2019).In West Central Coahuila, Mexico, a dried, preserved peyotl bottom, part of a necklace, was found in the Mayran mortuary complex, a multiple interment burial cave, suggesting the necklace was part of funerary offerings. The peyotl bottom was dated between 810 and 1070CE (Bruhn et al 1978, 1437). Analysis to identify its alkaloids revealed mescaline, the psychedelic principle in peyotl, but also chemical compounds including lophophorine, anhalonine, pellotine, and anhalonidine. Lithic and perishable items were also found at the site.Recent archeological excavations the La Morita II cave in Nuevo Leon, Mexico,, revealed an array of rock art manifestations from 6000 BCE. Archeologists explored this cave and concluded it had a mixed function as a funerary site and for daily life. “This deduction is based on the location of spears and projectile points to 4500 BP; remains of objects made from perishable materials, such as fragments of cordage and basketry from 300 BP. Other elements that contextualize daily life in the cave were coprolites (dried feces) and seeds of cacti, such as peyote and three species of the region.” (INAH, Newsletter 291, May 13, 2023).The sixteenth-century Florentine Codex (Geographical Reports of New Spain), the seventeenth-century Parecer de Juan de Salcedo sobre el Peyote, and Inquisition trial records describe cultural uses of peyotl that include medicine and divination as well as ritual and sacramental uses, Book X,, Chapter XXIX, of the Florentine Codex provides information regarding the knowledge developed by the Teochichimecas, who lived in the North: “And they knew the qualities, the essence, of herbs, of roots. The so-called peyote was their discovery. These, when they ate peyote, esteemed it above wine or mushrooms. They assembled together somewhere on the desert; they came together; there they danced, they sang all night, all day. And on the morrow, once more they assembled together. They wept; they wept exceedingly. They said [thus] eyes were washed; thus they cleansed their eyes” (Sahagún 1961, 173). Florentine CodexBook 11, Chapter VII, describes peyotl’s visionary properties.5. Interpretation

Considering the long history and wide array of Indigenous traditions, there is likely no single cult or homogenous ritual or ritual system for sacramental uses of peyotl(peyote). Ancient rituals have been registered for a number of Northern Mexico Indigenous peoples: Teochichimecas, Wixáricas, Coras, Raramuris, and Lipan Apaches. Ccolonial sources, however, show a clash of cultural paradigms between Indigenous cosmologies and the Catholic Church. According to Parecer de Juan de Salcedo sobre el Peyote—, written in 1619 by the rector of the Real y Pontificia Universidad, since the First Apostolic meeting of 1524 in Mexico, the Catholic Church has considered the sacramental use of peyotl to be an obstacle to evangelizing Indigenous peoples, because peyotl rituals and peyotl lore resemble ancient rituals and worldviews that pre-date Christianity in the New World. Peyotl and its sacramental use was officially banned by an inquisition edict in 1620, but one hundred inquisition trials record cultural uses of this sacred cacti during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In the nineteenth century, the peyotl cult spreads among Native American peoples in the Southwest United States. The spread of peyotl knowledge is recognized among Indigenous peoples in Oklahoma, mainly Comanches and Kiowas, but also among the Diné or (Navajos in Arizona).Peyotl knowledge is found in the prairies of Canada, notably in Saskatchewan, far from the Southwest United States.6. Implications

By the end of nineteenth century, the Native American Church of Jesus Christ (NAC) arose in the context of the banning of Ghost Song rituals in the United States. Members considered the sacramental use of peyotl (peyote) to be at the core of their ritual practices. The Native American Church of Jesus Christ gained official recognition by the United States government in 1918.The Native American Church emerged, to protect the religious freedom of its members. However, since the therapeutic properties in treating mental and spiritual health issues. (Calabrese 2012, 77-100). The peyotl cult grew rapidly among Native American peoples in Oklahoma. The United States government has attempted to make the NAC illegal, and many states introduced anti‐peyote legislation throughout the first half of the twentieth century. However, due to the NAC’s organization as a legal and recognized church, the result of protracted legal disputes, the NAC survives and thrives, increasing the number of church affiliates and winning court cases. The peyotl cult in the NAC has been considered a counter balance against colonialism. The NAC continues Furthermore another significant feature are their efforts to raise ecological awareness regarding the peyote preservation, for peyotl is now a plant species under threat. References:

Bruhn, J.G; Lindgren, J.E; Holmstedt, B and Adovasio, J.M. “Peyote Alkaloids: Identification in a pre-Historic Specimen of Lophophora from Coahuila, Mexico”. Science. Vol 199, No 4336.(Mar 31, 1978):1437-1438.

Calabrese, Joseph. D. A Different Medicine. Postcolonial Healing in the Native American Church. (Oxford University Press, 2013); 77-100.

Jay, Mike. Mescaline a Global History of the First Psychedelic (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 13-50.

Narváez Elizondo, R., Silva Martínez, L. E. y Breen Murray, W. “El brebaje del desierto: usos del peyote (Lophophora williamsii, Cactaceae) entre los cazadores-recolectores de Nuevo León”. Desde el herbario CICY, 10, (2018): 186-196. http://cicy.repositorioinstitucional.mx/jspui/handle/1003/2507

Rafferty, Sean M. (2018). “Prehistoric Intoxicants of North America.” In Scott Fitzpatrick (ed) Ancient Psychoactive Substances, (University Press of Florida, 2018): 112–27. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvx076mt.9.

Sahagún, Bernardino de. Florentine Codex (General History of the Things of New Spain). Book X. Trans by Charles E. Dibble and Arthur Anderson. (The School of American Research and the University of Utah 1961), 173.

Salcedo, Juan de, author. “Parecer De Dn Juan De Salcedo Sobre Peyote : En Consulta Que V.Sa Tuvo Se Confirio Sobre La Rayz Del Peyotly; El Efecto Que Causa y Obra Alos q Lo Toman y Beben Assi Yndios Como Españoles y Negros.” [Mexico City], 1619.

Schaefer, Stacy B, “The crossing of the souls. Peyote, Perception and Meaning among the Huichol Indians”. In Schaefer, Stacy B, Peter T Furst. (eds). People of the Peyote: Huichol Indian History, Religion, & Survival. (University of New Mexico Press, 1996):136-166.

Schultes, R.E, Hofmann, Albert and Rätsch. Plants of the Gods Their Sacred, Healing and Hallucinogenic Powers. (Healing Arts Press, 1992)

Image 1. Kauyumarie's Nierika. José Benítez Sánchez.Yarn Painting, 1974. Plywood, beeswax, and wool yarn. 122x122m. Photograph Juan Negrín. ©Wixarika Research Center. Notice the Nierika at the top of the image.

Image 2. Lophophora williamsii. Observation © Rodolfo Salinas Villarreal. Source: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/227875958

Image 3. Map

Image 4. Lophophora williamsii. Observation © altamiranohg. Source: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/245787140

It all begins with an idea. Maybe you want to launch a business. Maybe you want to turn a hobby into something more. Or maybe you have a creative project to share with the world. Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference. Don’t worry about sounding professional. Sound like you. There are over 1.5 billion websites out there, but your story is what’s going to separate this one from the rest. If you read the words back and don’t hear your own voice in your head, that’s a good sign you still have more work to do.